It usually begins with something small - a number that seems harmless enough.

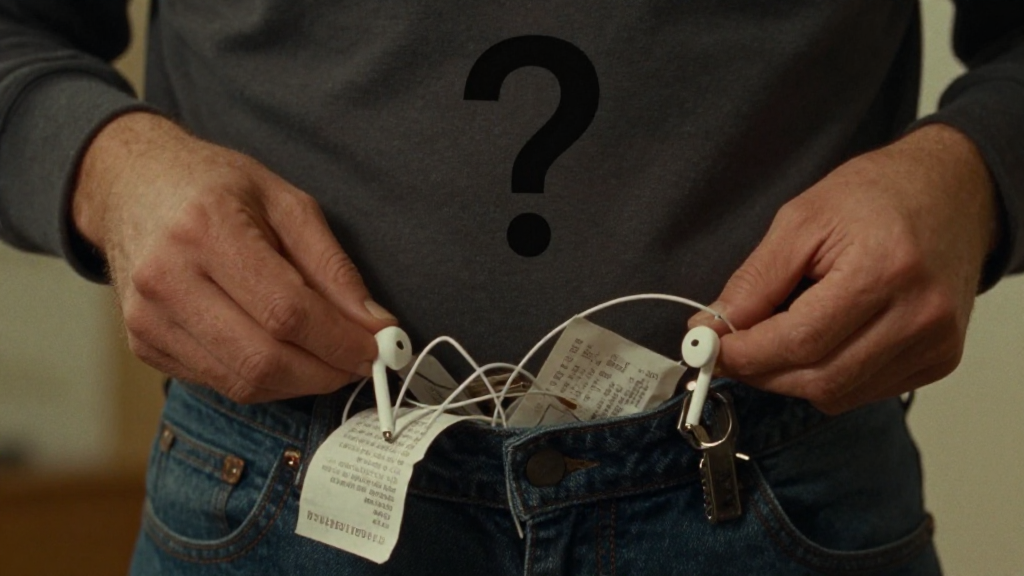

You're counting again.

Steps between rooms. Bites of food. How many times you've checked the lock. Your brain has become a relentless accountant, tracking things that don't need tracking, creating certainty where none is required.

At the gym, this same brain counts reps perfectly. You finish your sets, mark your progress, move on. The counting serves a purpose there-it helps you achieve something. But then you find yourself counting things that shouldn't need counting, following orders that no one gave you, checking things you already know are fine.

The counting happens automatically, without you deciding to do it. And when you try to stop, anxiety floods in so powerfully that giving in feels like the only option.

Here's what makes this particularly frustrating: you know the counting doesn't make sense. You understand logically that counting bites of food doesn't prevent anything bad from happening. Your conscious mind recognizes the absurdity, yet your brain keeps doing it anyway.

What's actually happening here? Why does knowing better not translate into doing better?

The Learning Loop Nobody Tells You About

What you can't see-what no one tells you about-is the learning process happening behind the scenes every single time you count or check.

Your brain is running a continuous experiment. And it's drawing conclusions from the data.

Here's the sequence: An intrusive thought appears. Maybe it's "Did I leave the stove on?" or "What if I'm eating too much?" The moment that thought lands, your anxiety spikes. Let's say it jumps from a 2 to a 7 on a 10-point scale.

That feeling is deeply uncomfortable. Your brain immediately searches for a way to reduce the discomfort. And it finds one: checking. Counting. Reviewing. You perform the ritual, and within seconds, the anxiety drops back down to a 3 or 4.

Relief.

What your brain learns from this sequence is simple and powerful: When I count (or check, or review), the discomfort goes away.

In neuroscience, this is called negative reinforcement-not punishment, but the removal of something unpleasant. It's one of the most powerful learning mechanisms your brain has. The behavior that reduces discomfort gets reinforced, strengthened, made more automatic.

Every time you complete a ritual and feel that relief, you're teaching your brain: "This works. Remember this. Do it again next time."

But here's the critical question that reveals the trap: If the counting and checking actually solved the problem, why does the anxiety always come back?

The answer exposes what's really happening. The ritual doesn't solve anything. It provides temporary relief, which is just long enough to teach your brain the wrong lesson, but not long enough to actually address what's driving the anxiety.

You're caught in a learning loop. And your brain is learning exactly the wrong thing from the experience.

Why Your Childhood Rules Created This Pattern

Now let's trace this pattern back to where it started.

From age 3 to 17, you grew up in an environment with rigid routines and controlling structures. Deviation from specific orders led to negative consequences. Your brain-doing exactly what brains are designed to do-learned powerful lessons during those formative years:

- Following rules keeps you safe

- Structure prevents bad outcomes

- Deviation is dangerous

- Pleasure is irresponsible

- There's always something more important than enjoyment

These weren't conscious choices. They were adaptations. Your brain was solving the problem in front of it: how to navigate an environment where strict adherence to order was required.

And it solved that problem brilliantly. You became highly skilled at maintaining structure, following specific orders, paying attention to detail. These capabilities serve you well now in certain contexts-your work performance, your gym routine, your ability to organize complex information.

But here's what's crucial to understand: the environment changed, but the learning remained.

The routines that were once imposed externally became internalized. What started as adaptation to external control transformed into self-imposed constraint. You're still following the rules, still maintaining rigid order, still experiencing anxiety when you deviate-except now, you're the one creating the rules.

Your brain isn't broken. It's not malfunctioning. It's doing exactly what it learned to do in an environment where those behaviors were necessary for safety.

The problem isn't that your brain learned. The problem is that it learned too well, and those once-adaptive responses are now causing distress in a context where they're no longer needed.

When Counting Helps (And When It Hurts)

This is the piece that almost no one talks about, the distinction that changes everything:

The counting itself isn't the problem.

Think about it. When you count reps at the gym, there's nothing wrong with that behavior. It's the same neural process-tracking numbers, maintaining accuracy, following a sequence. But the function it serves is completely different.

At the gym, counting is instrumental. It helps you achieve a goal: completing your workout, tracking progress, building strength. The counting serves the activity.

With food, or steps, or checking behaviors, the counting is protective. It's trying to prevent something bad from happening. It's trying to create certainty in uncertainty. It's trying to reduce anxiety about consequences.

Same behavior. Completely different function.

This distinction matters tremendously because it means you don't need to eliminate structured thinking. That would be throwing away a genuine strength. What needs to change is what function the structure serves.

When structure helps you achieve something-instrumental function-it's adaptive. When structure tries to prevent something bad-protective function-it maintains anxiety.

The sertraline you're taking helps reduce the intensity of the anxiety signal, which makes it somewhat easier to resist the urge to perform protective rituals. But the medication doesn't teach your brain new patterns. It creates a window of opportunity, but you still need to do the learning.

And that learning happens through gathering new evidence.

How to Teach Your Brain New Patterns

Here's what your brain currently believes based on all its accumulated evidence:

- Intrusive thoughts signal real danger that requires action

- Anxiety will continue escalating unless I perform the ritual

- The ritual is what makes the anxiety decrease

- Pleasure leads to negative consequences

These beliefs feel true because they're based on years of data. But the data is contaminated by the fact that you've always performed the ritual. You've never gathered clean evidence about what happens when you don't.

What if the anxiety decreases on its own, without the ritual? What if intrusive thoughts are just background noise, not important signals? What if pleasure doesn't actually lead to catastrophe?

You can't know the answers to these questions based on your current evidence. You need new data.

This is where your natural strengths become assets. You excel at organization, you appreciate scientific explanations, you're interested in psychology. You can leverage all of these by approaching your own mind like a research project.

The practice is called metacognitive observation-stepping back from your thoughts to observe them rather than being completely immersed in them.

Here's how it works:

When an intrusive thought appears, instead of immediately responding with a ritual, you observe and record:

- What's the thought?

- What's your anxiety level right now (0-10 scale)?

- How strong is the urge to perform the ritual (0-10 scale)?

- If you wait 10 minutes without performing the ritual, what happens to the anxiety level?

- What actually happens versus what you feared would happen?

You're creating a data set. You're testing the hypothesis that anxiety might decrease naturally without the ritual.

This isn't about willpower or forcing yourself to stop. It's about curiosity. What does the evidence actually show?

Additionally, you can run behavioral experiments on your beliefs about pleasure. Choose one meal this week based on what you want rather than what you "should" eat. Before you eat it, write down what you predict will happen (the feared consequence). Then document what actually happens.

Your brain learns from experience. Right now, it has extensive experience with one pattern: thought → anxiety → ritual → temporary relief → anxiety returns. You're giving it the opportunity to learn a different pattern: thought → anxiety → observation → anxiety decreases naturally → no catastrophe occurs.

With repeated experiences, the old neural pathway weakens. The new pathway strengthens. This is neuroplasticity-the same mechanism that created the current patterns can create different ones.

The timeline isn't instant. Strong pathways that formed over years through countless repetitions need time and repeated new experiences to change. But they do change, measurably and sustainably, when the learning conditions are right.

What Happens When the Patterns Finally Change

Imagine having the mental energy you currently spend on rituals available for things that actually matter to you. Your psychology learning. Enjoying activities without constant monitoring for whether you're doing something wrong. Choosing food because you want it, not because it fits a mental checklist.

This isn't about eliminating your attention to detail or your organizational abilities. Those remain strengths. What changes is where and how you deploy them-toward instrumental functions that help you achieve things, not protective functions that try to prevent imagined catastrophes.

You mentioned interest in the possibility of not needing medication indefinitely. Here's what the research shows: medication creates favorable conditions for learning by reducing the intensity of the anxiety signal. But lasting change comes from behavioral practice that retrains the neural pathways. Successful outcomes typically involve using medication as a scaffold while building new patterns, then gradually reducing medication as the new patterns become established.

The question you asked at the end of the conversation reveals the next level of understanding you need: How long does pathway reformation take, and do setbacks undo progress?

The answer involves surprising findings about how your brain actually consolidates new learning. Setbacks aren't failures-they're part of the learning process, and your brain is drawing conclusions even from attempts that feel like "failures." There's also fascinating research about the minimum viable practice needed to maintain new patterns, and what distinguishes people who achieve sustainable flexibility from those who remain dependent on external supports.

But that's a different conversation.

For now, you have what you need to start: understanding of the mechanism maintaining the current patterns, and a specific practice for gathering new evidence that can teach your brain different lessons.

Your brain learned these patterns. That same brain can learn new ones.

The data collection starts now.

What's Next

Stay tuned for more insights on your journey to wellbeing.

Comments

Leave a Comment