But here's what you can't see: the price you just paid.

What You Think Is Causing It

When you can't perform at your old level—when the work that used to flow now feels like pushing a boulder uphill—the obvious conclusion seems clear: you're not trying hard enough.

Maybe it's age. Maybe it's lack of discipline. Maybe you've just gotten soft. The solution feels equally obvious: push harder. Maintain your standards. Don't let yourself slip.

If you have an engineering background, you might even frame it technically: your current output doesn't match your peak 20-year-old output, therefore you need to increase input effort to compensate. It's basic math.

Except it's not. And if you've been pushing harder for months or years without getting back to your old performance level, you've probably already discovered that something in this equation is wrong.

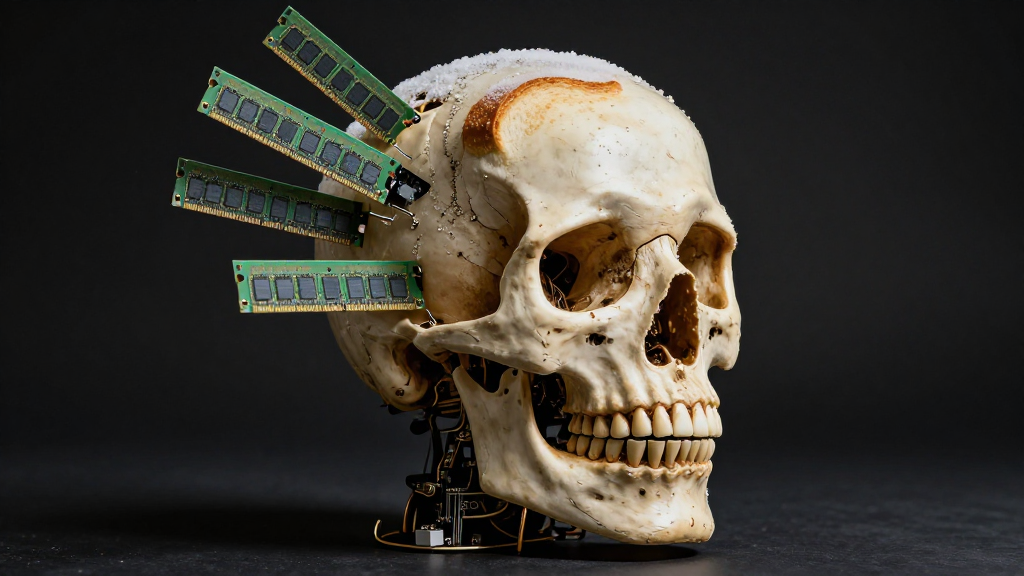

Why You Wouldn't Run Hardware This Way

Imagine a client hands you a circuit board. They want you to evaluate whether it can handle a particular workload. You run the diagnostics:

- The board has sustained component damage from overheating

- Several subsystems are operating at reduced capacity

- The cooling system is compromised

- Current baseline temperature runs 15-20% higher than specification

Then they tell you they want to run this board at 110% of its original rated load. Continuously. With no additional cooling.

What would your professional recommendation be?

You'd tell them it's a recipe for catastrophic failure. You'd explain thermal runaway, reduced component lifespan, and unpredictable errors. No competent engineer would sign off on that operating plan.

Now here's the uncomfortable question: Why are you running yourself that way?

The Truth About Forcing Focus

Here's what's actually happening when you force focus through dread and anxiety:

Your brain doesn't have a "try harder" button. What it has is a stress response system. When you feel dread about a task but force yourself to do it anyway, you're not accessing some reserve willpower tank. You're activating your HPA axis—your body's central stress response.

Research on cognitive load under chronic stress shows something that sounds paradoxical: when you force concentration through anxiety-driven vigilance rather than genuine cognitive readiness, you activate a continuous cortisol response. Studies measuring cortisol patterns in stressed professionals show that this "pushing through" approach elevates baseline cortisol by 40-60%.

Now here's the part that changes everything: elevated cortisol directly impairs the prefrontal cortex functions you're trying to optimize. Working memory. Executive function. Error detection. The very cognitive capacities you need for focused work.

You're not just working harder to get the same result. You're actively degrading the processor while trying to run it faster.

In engineering terms, you're getting a 1:20 return on investment. You gain 10% more speed but generate 200% more heat. No engineer would ever approve that design. The heat dissipation alone would require massive cooling systems, and you'd still be shortening component life.

But that's exactly what "pushing through" does to your brain.

The Perfectionism Mistake That Drains Your Battery

There's a second hidden cost in how you're operating, and it shows up in what you might call your quality control approach.

If you're anything like the engineering professionals I work with, you probably have what I call a Zero-Tolerance Policy for mistakes. A typo in an email gets the same vigilant attention as a safety-critical calculation. Every task receives 100% monitoring energy. Every error feels like a failure.

This sounds like conscientiousness. It feels like professionalism.

But here's what it actually is: catastrophically inefficient resource allocation.

In your engineering work, do you actually apply the same inspection rigor to every single component? Or do you use statistical process control—identifying critical failure modes for intensive monitoring while sampling non-critical variations?

Of course you use statistical process control. You know that if you tried to measure everything at maximum precision, you'd never ship a product and the inspection cost would exceed the product value.

Research on perfectionism and cognitive efficiency shows that undifferentiated vigilance—treating all errors as equally catastrophic—consumes roughly 3x the attentional resources of risk-stratified monitoring, while providing only marginal improvement in catching truly critical errors.

Think about that ratio. You're spending three times the mental energy for maybe a 5% improvement in outcomes on tasks that don't matter.

You're running every system at 100% power when a tiered approach would give you 95% of the benefit at 33% of the cost.

Why Willpower Can't Fix Damaged Hardware

Now layer in one more factor: your current hardware isn't just "older." It's operating with documented damage.

Neuroimaging studies of individuals recovering from COVID-related cognitive effects show persistent changes in the default mode network and reduced connectivity in attention networks for 12+ months post-infection. Depression further reduces available dopaminergic and noradrenergic signaling—these are literally the neurotransmitters that support sustained attention and task-switching.

This isn't a metaphor. Your hardware is running with:

- Reduced bandwidth in critical networks

- Lower neurotransmitter availability

- Slower processing speeds

- Higher baseline activation costs

And you're asking it to perform at 2019 specifications.

Here's what makes this particularly insidious: the gap between your expected performance and your actual output feels like evidence that you're not trying hard enough. So you push harder, which activates more stress response, which further degrades the exact cognitive functions you're trying to access.

It's not a motivation problem. It's a design problem. You're trying to run high-demand software on lower-capacity hardware, and your compensation strategy is actively making the hardware worse.

The Derating Principle You're Ignoring

There's a standard practice in engineering called derating. When you expect a component to operate in harsh environments, you don't run it at maximum rated capacity. You run it at 70-80% of spec to ensure reliability.

You know this principle. You use it in your work.

So here's the thought experiment: If your current cognitive capacity is already reduced from COVID effects, depression, and caregiver stress—and you're juggling four professional roles—what should your derating calculation look like?

Not what you wish it could be. What actual engineering analysis would recommend.

Most professionals I work with, when they actually run the numbers, discover they should be allocating roughly 50-60% of their pre-2019 capacity to each current commitment. Not because they're weak. Because that's what the math says when you account for reduced baseline capacity and the need for operational margin.

Now add up four roles at even 50% allocation each. You get 200% of available capacity. The system is mathematically overloaded before you even account for the efficiency loss from context-switching.

The performance gap you're experiencing isn't a motivation problem. It's not a discipline problem. It's a basic load engineering violation.

What You'd Tell Someone Else

Here's one of the most interesting findings in psychological research: people give much wiser advice to others than they follow themselves. It's called Solomon's Paradox, and it happens because psychological distance allows us to think more analytically and less emotionally.

So let's create that distance.

Imagine a colleague comes to you with this exact situation: post-COVID cognitive effects, depression, caregiver stress, attempting to maintain four professional roles at pre-2019 performance levels while using anxiety-driven focus to compensate for reduced capacity.

You're the outside consultant evaluating their system. What would your professional recommendation be?

If you're honest, you'd probably flag immediate violations of basic load engineering principles. You'd recommend scope reduction of 25-40% of current commitments. You'd definitely identify the overclocking behavior as high-risk. And you'd probably note that they're being harder on themselves than they'd ever be on actual hardware—engineers build in margins and safety factors, but they're running at theoretical maximum with no buffer.

Notice how clear your judgment becomes when you evaluate someone else's system versus your own?

So here's the question: What makes you exempt from good engineering practice?

How to Actually Fix This

The solution isn't magical. It's not even particularly complex. But it does require you to treat yourself with the same professional objectivity you'd apply to any other system analysis.

Research on self-compassion shows that individuals who apply engineering-level objectivity to their own capacity constraints actually recover function faster and sustain higher long-term performance. They're not being "soft"—they're being correctly calibrated.

Here's what correct calibration looks like:

First: Implement Statistical Process Control for your attention

Categorize your tasks into three tiers:

- **Critical** (safety, client deliverables, financial obligations): 100% monitoring energy

- **Moderate** (professional quality, relationship maintenance): 50% monitoring energy

- **Low-consequence** (cosmetic errors, minor inefficiencies, typos): 20% monitoring energy

That email typo? It's not a safety failure. It's a cosmetic defect. It gets 20% of your quality control energy, not 100%.

Track this for one week. Record your anxiety levels (0-10 scale) and actual error rates in each category. You'll probably discover that reducing monitoring on low-consequence tasks doesn't increase error rates—it just reduces your stress by 60-70%.

Second: Run your actual derating calculation

Estimate your current cognitive capacity relative to your pre-2019 baseline. Account for COVID effects, depression, caregiver stress. Be honest about what the hardware can actually do.

Then apply a 50-60% derating factor for sustainable operation. (Remember: derating isn't pessimism, it's reliability engineering.)

Now map that derated capacity across your four current roles. Assign realistic percentages.

If your total exceeds 100%, you have mathematical proof that your current role allocation is unsustainable. That's not a motivation problem. That's a capacity problem, and it requires scope reduction, not increased effort.

Third: Write the consultant's memo

Take 20 minutes and write a one-page professional recommendation as if you were evaluating someone else's workload with your exact constraints. Be specific about scope reduction. Note the risks of current operating conditions.

Then ask yourself: Would you implement these recommendations for a client? Would you sign off on a system design that violated these principles?

If not, what makes you exempt?

What Happens When You Stop Overclocking

Here's what happens when you actually engineer for your current capacity instead of trying to override it:

Your baseline cortisol drops. Your prefrontal cortex functions recover. Your actual cognitive performance improves because you're no longer actively degrading it with chronic stress.

You make the same number of critical errors (or fewer), but you stop wasting energy on non-critical monitoring. Your overall stress decreases by 40-60% while your meaningful output stays stable or improves.

And perhaps most importantly: you stop interpreting the gap between current and past performance as evidence of moral failure. You start seeing it as what it actually is—a hardware specification problem that requires engineering solutions, not willpower.

The math was never going to work with your current allocation. The only question is whether you're going to keep running the system until it fails catastrophically, or whether you're going to apply the same professional standards to yourself that you'd apply to any other overloaded system.

You already know what the professional recommendation would be.

The question is whether you'll actually implement it.

What's Next

Stay tuned for more insights on your journey to wellbeing.

References

- Grossmann, I., & Kross, E. (2014). Exploring Solomon's paradox: Self-distancing eliminates the self-other asymmetry in wise reasoning about close relationships in younger and older adults. Psychological Science, 25(8), 1571-1580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614535400

Comments

Leave a Comment