Your therapist says it's depression. Your psychiatrist adjusted your medication. You're trying. You're doing everything right. And yes, you feel less sad than you did six months ago. But you still can't think like a lawyer, and thinking like a lawyer is the only thing that matters.

Is your brain permanently damaged? Or is there something about depression and cognitive function that no one has explained to you?

The Old Belief: Fix the Mood, Fix the Mind

Here's what most people-including most patients and many clinicians-believe about depression and cognitive function:

Depression is fundamentally a mood disorder. You feel sad, hopeless, empty. The cognitive problems-the foggy thinking, the memory lapses, the difficulty concentrating-are symptoms of that mood disturbance. They're downstream effects. So the logic goes: treat the depression, lift the mood, and the thinking problems will resolve themselves.

This makes intuitive sense. When you're deeply sad, of course it's harder to focus. When you're exhausted from depression, of course your memory suffers. The cognitive impairment is part of the depression, not separate from it.

So you take the antidepressant. You go to therapy. You work on your mood. And you wait for your brain to come back online.

This is what you've been doing. This is what your treatment team has been addressing. The mood symptoms have improved-you're less sad, less hopeless than you were. So why can't you still hold multiple threads of a legal argument in your head? Why do you still lose track midway through complex reasoning?

If the model is correct, your cognition should have improved with your mood.

The New Reality: Two Systems, Two Problems

Here's what research has revealed over the past decade:

Mood symptoms and cognitive symptoms in depression are related but dissociable. They don't always move together. They can improve at different rates. And they often require different treatments.

Studies show that even after someone's mood symptoms have responded to treatment-even after they meet criteria for "remission" from depression-39 to 44 percent still have significant cognitive difficulties. Not mild problems. Significant impairment in attention, memory, and executive function.

Let me say that differently: nearly half of people who successfully treat their depression still can't think clearly.

This isn't because the antidepressant didn't work. It's because medication and psychotherapy primarily target mood and emotional regulation. They address neurochemistry. They help with the sadness, the hopelessness, the emotional pain.

But cognitive function-particularly executive function, which includes things like working memory, cognitive flexibility, and planning-operates through different neural circuits. These circuits are also affected by depression, but they don't automatically repair when mood improves.

What you're experiencing makes perfect sense. You've described having "relatively okay days mood-wise" while still being unable to focus on a brief. That's not a failure of treatment. That's two separate systems responding differently to the same disease process.

The old belief says: depression is one problem with many symptoms.

The new reality says: depression affects multiple distinct systems that need to be addressed as separate treatment targets.

The Method That Matches: Target Cognition Directly

If cognitive symptoms are separate from mood symptoms, then waiting for mood treatment to fix your cognition is backwards.

The conventional approach follows this sequence:

- Treat the depression (medication, therapy)

- Monitor mood symptoms

- Wait for cognitive improvement as a downstream effect

- Hope that thinking returns to baseline

But here's what actually works better:

- Treat depression's mood symptoms (medication, therapy)

- Separately assess and treat cognitive symptoms (neuropsychological testing, cognitive rehabilitation)

- Target specific executive function deficits with evidence-based cognitive training

- Use strategic external supports while retraining neural pathways

- Measure both mood and cognitive improvement as distinct outcomes

The reversal is this: instead of treating mood and hoping cognition follows, you treat both as primary targets from the beginning.

Cognitive rehabilitation directly trains the executive function skills that depression has impaired. Research shows that neuroplasticity-based cognitive remediation can improve executive function measures more effectively than medication alone-and in some studies, it improves depressive symptoms as quickly as antidepressants while simultaneously rebuilding cognitive capacity.

You don't just wait for your brain to heal. You actively retrain it.

This is why "trying harder" hasn't worked. You've been waiting for the fog to lift so you can function normally again. But working memory-the ability to hold multiple threads of argument in your head-isn't something that passively returns. It's something that can be systematically strengthened through graduated exercises designed to rebuild those specific neural pathways.

The method that matches the problem is this: treat what's impaired, not what you hope will spontaneously recover.

The Detail That Seals It: Physical Changes, Plastic Capacity

Now here's the piece that explains both why this is happening and why rehabilitation works:

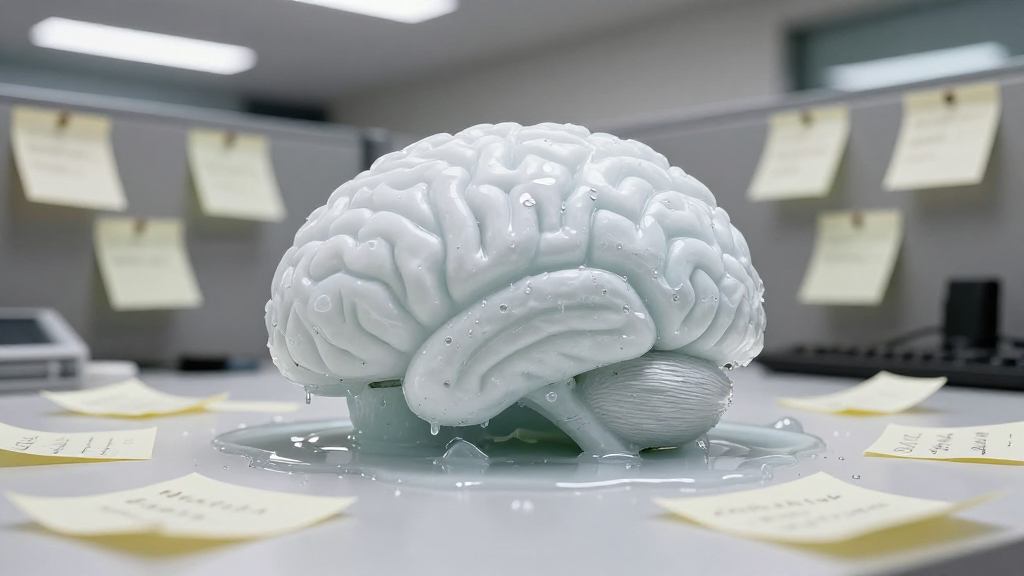

Depression causes measurable physical changes in your brain. Research demonstrates reduced synaptic connections between neurons, decreased dendrites, and atrophy in specific regions-particularly the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, areas critical for memory and executive function.

When you say "Is my brain damaged?" you're asking the right question. There are physical changes. The impairment you're experiencing isn't "all in your head" in the dismissive sense-it's neurological.

But here's the critical detail almost no one mentions:

Your brain isn't like a broken bone that heals to its original state. But it's also not like a shattered vase with permanent damage. The brain has something called neuroplasticity-the capacity to form new connections, build new pathways, and adapt its structure in response to experience and training.

You didn't always think like a lawyer. Your brain built those analytical pathways through years of legal training and practice. You developed the ability to hold multiple threads of argument, to track precedent and statute simultaneously, to shift between different legal frameworks.

If depression has weakened those pathways-reduced the synaptic connections that support complex legal reasoning-then those pathways can be rebuilt. Not passively. Not by waiting. But through targeted practice that leverages the brain's neuroplastic capacity.

This is why cognitive rehabilitation works. You're not trying to "fix" a broken brain. You're actively rebuilding the neural infrastructure that supports the cognitive skills you need.

The forgotten factor is this: depression treatment addresses the neurochemical environment, but cognitive rehabilitation addresses the neural architecture. Most treatment plans focus exclusively on the first and completely overlook the second.

Your psychiatrist is managing your antidepressant to optimize neurotransmitter function. That's essential. But no one is directly targeting the weakened executive function pathways or systematically training your brain to rebuild working memory capacity.

That's the missing piece.

Without This: The Path of Partial Recovery

If you continue treating only the mood symptoms, here's what the trajectory looks like:

Your depression continues to improve. The deep sadness lifts. You have more energy, more motivation, more hope. Your psychiatrist considers the treatment successful. By the clinical definition, you might even reach "remission."

But you still can't prepare legal arguments the way you used to. You still lose track of complex reasoning. You still read paragraphs three times and retain less than you did before depression.

You develop workarounds. More detailed notes. More external reminders. Simpler cases. You tell yourself you're "managing" and that this is "good enough."

Your managing partner notices you're not performing at your previous level but attributes it to the depression you've been open about. You don't correct this because you don't know how to explain that you're less depressed but still impaired.

Years pass. The cognitive deficits persist because they were never directly addressed. You adapt to a diminished professional capacity, eventually accepting this as your new baseline. The fear you felt in the beginning-Is this who I am now?-becomes a quiet certainty.

You don't stop being a lawyer. But you stop being the kind of lawyer you were.

With This: The Path of Comprehensive Recovery

Here's what becomes possible when you treat mood and cognition as separate but connected targets:

You talk to your psychiatrist specifically about your executive function deficits-not just "I can't concentrate" but "I can't hold multiple threads of reasoning, I can't track argument structure, I lose my place in complex analysis." You request neuropsychological testing to establish a baseline measure of which specific cognitive functions are most impaired.

The testing reveals exactly what you suspected: significant deficits in working memory and cognitive flexibility, moderate impairment in planning and organization. But now you have objective data. You know what needs to be targeted.

You work with a neuropsychologist who specializes in cognitive rehabilitation for mood disorders. You learn that your working memory-that ability to hold multiple argument threads simultaneously-can be trained through specific exercises that gradually increase cognitive load. You practice attention-switching tasks that rebuild the flexibility you've lost. You work on prospective memory strategies that help you remember to execute the intentions you form.

This isn't "brain training games." This is systematic, graduated practice designed to rebuild the specific executive function systems that legal reasoning demands.

Simultaneously, you implement strategic external supports. You develop a systematic note-taking structure that compensates for working memory limitations while you're rebuilding capacity. You use visual workflow aids for complex cases. You schedule reminders for crucial deadlines.

You continue your depression treatment. The mood continues to improve. But now, the cognition is also improving-not as a hopeful side effect, but as a directly measured outcome.

Three months in, you notice you're re-reading paragraphs less frequently. Six months in, you can hold three related arguments in your head simultaneously, then four. Your neuropsychological testing shows objective improvement in executive function measures.

You have a conversation with your managing partner that reframes your situation: this isn't about being "less capable" due to depression. This is about recovering from a neurological symptom that you're actively treating with evidence-based rehabilitation.

You don't just manage your impairment. You systematically address it. Your professional capacity doesn't just adapt to a lower baseline-it recovers toward your previous level of function.

The First Move: Make Cognition Visible

The single step that separates these two paths is this: make your cognitive symptoms visible as a separate treatment target.

Right now, "I have depression" encompasses everything-mood, energy, cognition, motivation. It's all folded into one diagnosis. But that obscures the fact that you have two related but distinct problems that need distinct interventions.

Your first move is to separate them.

Schedule a conversation with your psychiatrist specifically about cognitive symptoms. Don't say "I'm still having trouble concentrating." Say:

"I want to discuss the cognitive dimension of my depression separately from the mood symptoms. My mood has improved, but I still have significant executive function deficits-specifically problems with working memory, cognitive flexibility, and prospective memory. I can't hold multiple threads of reasoning the way I could before depression. I'd like to request neuropsychological testing to establish a baseline, and I want to discuss cognitive rehabilitation options that directly target these deficits."

That conversation changes everything. It reframes your treatment from "manage depression" to "treat mood symptoms AND cognitive symptoms as two connected but separate targets."

Your brain isn't gone. It's impaired by an active disease process that's affecting both your neurochemistry and your neural architecture. One is being treated. The other has been overlooked.

The first move is making the overlooked become visible.

What's Next

In our next piece, we'll explore how to apply these insights to your specific situation.

Comments

Leave a Comment