You're staring at your to-do list. Again.

You know exactly what needs to be done. The tasks aren't even that complicated—most of them are things you could knock out in thirty minutes if you could just... start. But instead of picking something and moving forward, you feel a kind of dread settling in. Your mind goes blank. The list sits there, and you sit there, and nothing happens.

If you're like most high-performers dealing with this, you've probably blamed yourself. I just need to be more disciplined. I need better time management. I need to stop procrastinating.

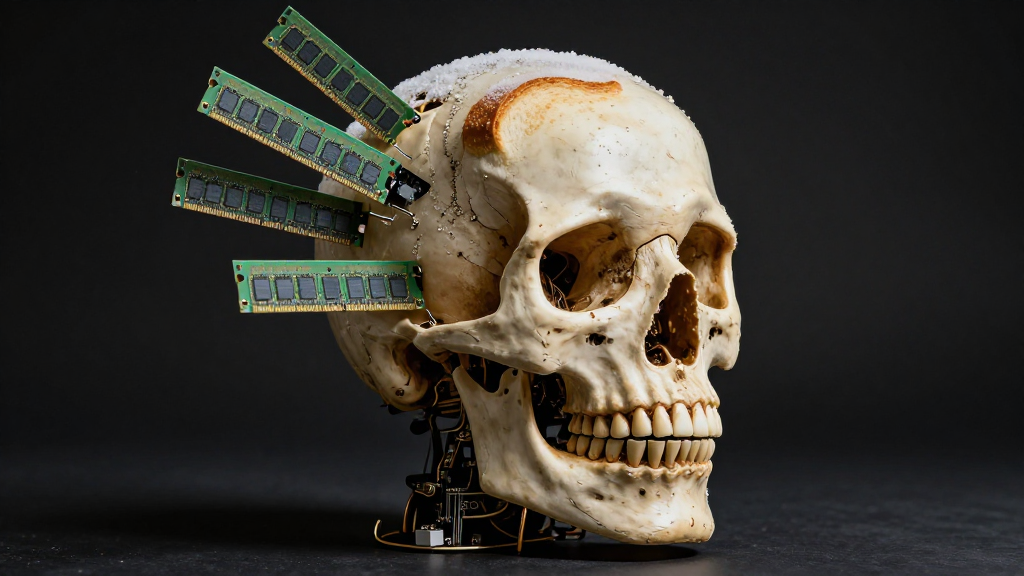

But here's what's actually happening: you're not experiencing a personal failing. You're experiencing predictable system behavior when a computer is running too many processes with insufficient RAM.

What Nobody Tells You About Mental Overload

Think about what happens when you're in the middle of actual engineering work—designing a system, architecting a solution, debugging a complex problem. If you try to load too many variables into active consideration at once, what happens?

The design quality tanks. You either miss critical interactions between components, or you freeze completely and can't make progress. You instinctively reach for a whiteboard to externalize the relationships, because you know you can't hold them all in your head simultaneously.

You recognize this as a limitation of your cognitive architecture, not a character flaw. You don't think "I'm bad at engineering because I need to draw diagrams." You think "Complex systems require external representation to manage effectively."

So why, when it comes to your own task management and mental state, do you treat the same limitation as a personal failure?

The Working Memory Mistake You're Making

Current research on working memory puts functional capacity at approximately 4 to 7 distinct chunks of information. That's not a metaphor. That's the actual measured capacity of your brain's active processing space—the cognitive equivalent of RAM.

Now do a quick inventory. Right now, in your head, how many things are you actively tracking?

- Four different job projects with varying statuses

- Your parents' health situation and upcoming medical appointments

- Your own energy levels and that nagging sense of fatigue

- The growing list of tasks you need to complete

- The emails you haven't responded to yet

- That thing you forgot to do yesterday that's still bothering you

How many chunks is that? At minimum, six. More realistically, closer to ten or fifteen if you break them down into their actual components.

You're already at capacity before you even try to do actual work.

And when you hit capacity in a computer system, what happens when you try to load one more process?

System freeze. Thrashing. The computer starts swapping everything in and out of active memory, burning processing cycles on memory management instead of actual computation. Performance drops by 40-80%. The system runs hot, slows down, and barely makes any progress despite consuming massive amounts of energy.

That feeling of dread when you look at your to-do list? That's not anxiety. That's not laziness. That's the phenomenological experience of executive function failure under cognitive overload.

Studies on cognitive fatigue demonstrate measurable impairment in executive functions—the parts of your brain that select tasks, initiate action, and switch between contexts—when working memory is overloaded. Healthcare professionals working on-call shifts describe exactly what you're experiencing: slowed processing time, deficits in working memory, and overall impaired executive functioning when cognitive load is too heavy.

Your brain isn't broken. It's a system running at 110% capacity, and it's behaving exactly as system architecture predicts.

The Truth About Context Switching

Let's talk about context switching.

Someone sends you an email. You read it and respond. Two minutes, tops. A Slack message comes in. You answer it. Another ninety seconds. Then you try to get back to the design work you were doing.

Seems efficient, right? You're staying on top of communication while still making progress on your core work.

Except research on task switching reveals something most people don't see: it takes more than 25 minutes to fully resume a task after being interrupted. And when you're switching contexts frequently, productivity can drop by 40 to 80 percent.

Think about that from a systems perspective. What happens when an operating system is constantly interrupting processes, saving state, loading new contexts, then reversing it all?

You get thrashing. Most of the CPU time goes to context management instead of actual work. The system runs hot, gets slow, and barely makes progress on any individual task.

Every time you "just check email real quick," you're forcing a full context save and load. The mental state you had for the design work—all the variables you were holding, the solution space you were exploring, the relationships you were considering—gets swapped out. Then you load in the email context: who this person is, what they're asking, what the appropriate response is, the tone you need to use.

Then you swap it all again to get back to the design work.

But here's the part most people miss: the swap isn't clean. Researchers call it "attention residue." Part of your attention stays stuck on the previous task. The email you just sent, the question you just answered—fragments of it remain in your working memory, consuming resources that should be available for the work you're trying to focus on.

If you're switching tasks every 10 minutes during an 8-hour workday, you're spending more time managing context switches than doing actual work. The 40-80% productivity loss isn't a metaphor. It's a measured outcome.

And when you're already running on low energy? When your baseline cognitive capacity is reduced by fatigue? That context switching cost becomes absolutely devastating.

Why Writing Things Down Actually Works

Most productivity advice tells you to write things down. Make lists. Keep a journal. Externalize your thoughts.

You've probably tried this. Maybe it helped a little. Maybe it didn't stick.

Here's what most people don't understand about why this works: Writing things down isn't organizational. It's neurological.

When you're holding a task in your head—"Don't forget to call about Dad's test results"—your brain is running a background process. One of your precious 4-7 working memory chunks is allocated to "keep this information active." It's not available for decision-making, problem-solving, or creative thinking. It's just... sitting there, holding that information.

When you write it down on a physical piece of paper, something specific happens in your brain. Research on cognitive offloading shows that externalizing information genuinely frees neural resources. The working memory slot that was running "remember this task" gets deallocated. It becomes available for actual cognitive work.

This isn't just "feeling more organized." Experimental studies show that offloading working memory increases the amount of information that can be maintained and releases resources that can be used for processing subsequent tasks. Cognitive performance measurably improves.

But there's a second mechanism at play, particularly with worries and anxious thoughts.

Studies on expressive writing—specifically writing about worries and concerns—reveal something remarkable: it reduces the size of error-related negativity brain signals in people who worry frequently. When chronic worriers wrote briefly about their thoughts and feelings before a stressful task, they performed better and showed reduced anxiety markers in brain activity.

The leading theory? Writing "offloads" worrisome thoughts, freeing up mental resources to concentrate on tasks at hand.

Your brain can stop running the "don't forget to worry about this" process and allocate those resources to "decide what to do next."

This is why your coach prescribed the "Worry Buffer" system—that notepad where you write down intrusive worries with a note like "Data saved. Will process at 5:00 PM."

It sounds like a psychological trick. But it's explicit memory management. You're telling your brain: "This information is stored externally. You don't need to keep running this process. Deallocate this chunk."

And your brain... complies. Because that's how the system works.

The Hidden Cost of Visible To-Do Lists

Here's a question: if you've already written your master task list down—if you've already externalized it to free up working memory—why would hiding it make any difference?

The answer reveals something important about how cognitive load works.

Visual information competes for attention and working memory even when you're not consciously engaging with it. When your master list with 40 items is sitting there in your peripheral vision, your brain is processing it at some level. Not actively, not deliberately, but it's still consuming resources.

Your brain sees those items and tries to assess them, prioritize them, feel anxious about them. It's like having 40 browser tabs open—even if you're only actively using one, they're all consuming memory and processing power.

The "One Monitor" rule—writing your single current task on a sticky note and physically hiding the master list—creates a clean working environment with minimal cognitive overhead. You've eliminated the passive processing cost of having all those options visible.

This matters more than most people realize, especially when you're operating on reduced cognitive capacity due to fatigue.

How to Stop Blaming Yourself for System Overload

So let's reframe everything.

You're not failing at productivity because you lack discipline. You're experiencing well-documented system behavior when a computer with 8GB of RAM tries to run 12GB of processes.

You're not being lazy when you can't start tasks. Your executive function is measurably impaired because your working memory is already maxed out.

You're not wasting time when you spend 90 minutes on a single task without interruptions. You're avoiding the 40-80% productivity loss that comes from constant context switching.

You're not relying on "productivity hacks" when you write things down. You're implementing evidence-based cognitive offloading strategies that demonstrably improve executive function performance.

This is engineering, not self-improvement.

You wouldn't expect a server to run smoothly with insufficient resources. You wouldn't blame the hardware for failing when the software demands exceed system capacity. You'd recognize it as a system architecture problem and implement appropriate solutions: add more RAM, optimize processes, reduce concurrent operations, implement better resource management.

The same logic applies to your cognitive architecture.

On low-energy days when you're running at 4 out of 10 instead of 8 out of 10? Your working memory capacity is already compromised by fatigue. That's not weakness. That's measured cognitive impairment under load. The research shows this clearly: acute cognitive fatigue significantly impairs both motor control and executive control.

On those days, you need to be even more disciplined about what you load into your limited RAM. Not because you're failing, but because you're working with reduced specifications.

Four Ways to Fix Your Mental RAM Problem

Once you understand the system constraints, the solutions become obvious.

Solution 1: External Storage (Brain Dump + Master List)

You can't think your way out of RAM overload. The very act of trying to solve it mentally consumes the limited RAM you have. You need to dump everything out of active memory onto persistent storage.

Tonight, before you sleep: write everything down. Every task, every worry, every "don't forget," every project status, every parental health concern. Everything that's taking up space in your head goes onto paper.

This isn't optional. This is a memory management requirement.

Solution 2: Single-Process Execution (The One Monitor Rule)

From that master list, select ONE task for your first 90-minute block tomorrow. Write only that task on a sticky note. Then physically hide the master list.

Only one task visible. Only one thing loaded into active memory. Clean working environment.

Solution 3: Interrupt Protection (Batch Processing)

During that 90-minute block: phone in another room, email closed, single browser tab if needed. If a worry or urgent thought intrudes, write it on your Worry Buffer notepad with a specific processing time ("Will review at 5:00 PM"), then immediately return to your primary task.

You're not ignoring important things. You're saving them to external storage and scheduling a dedicated processing cycle. That's proper resource management.

Why 90 minutes? Because context switching has a high upfront cost. If you're going to pay that cost anyway, you want to amortize it over substantial work. Ninety minutes lets you pay the context-load cost once, then actually use your full working memory for the problem at hand.

No thrashing. No attention residue. Just clean, focused computation.

Solution 4: Scheduled Worry Processing

At 5:00 PM (or whatever time you choose), do a 15-minute review of your Worry Buffer. Look at each item and triage it: Is this a Critical Failure (Q1)? Core Job responsibility (Q2)? Just Noise (Q3)? Or Junk Data (Q4)?

Your brain's urgency detection system can't tell the difference between "urgent" and "important." Research on the "mere-urgency effect" shows that attention is drawn to time-sensitive tasks over less urgent ones, even when the less urgent task offers greater rewards. Email feels urgent. Slack messages feel urgent. But your core engineering work is what's actually important.

By scheduling specific processing time for interruptions and worries, you're overriding that urgency bias with a deliberate prioritization protocol.

What Happens When You Protect Two 90-Minute Blocks

Let's do the math on what happens when you protect just two 90-minute blocks per day with zero context switching.

Your current baseline: switching tasks every 10 minutes during an 8-hour day. With 40-80% productivity loss from context switching, you're getting somewhere between 1.6 and 4.8 hours of effective work done.

Two protected 90-minute blocks: 3 hours of guaranteed effective work time, with zero context-switching loss during those blocks.

Two focused blocks potentially match or exceed your current full-day output.

Not because you're working harder. Because you're not burning half your processing power on memory management overhead.

And here's what else changes: the decision paralysis when looking at your to-do list starts to decrease. Because you're not asking your already-maxed-out working memory to also handle task selection. You made that decision during your morning review when your RAM was clear.

The dread starts to lift. Not because you've developed superhuman discipline, but because you've stopped asking your executive function to operate under conditions that guarantee failure.

Can You Actually Increase Your Mental RAM?

You're working within today's constraints. You're implementing appropriate engineering solutions for a system with known limitations.

But here's what the research also shows: more than 79% of meta-analyses demonstrate that training programs targeting executive function are effective, with small to medium improvements in capacity.

If working memory capacity is currently limited... can it be systematically increased?

If context switching is expensive now... can that cost be reduced through specific protocols?

If decision fatigue is draining your battery... are there interventions that build decision stamina over time?

You're not stuck with your current specifications. But you do have to work within today's constraints while you build tomorrow's capabilities.

For now: treat yourself like the complex system you are. Respect the limitations. Implement the engineering solutions. Stop expecting your brain to violate its own architecture.

The freeze isn't failure. It's data. And now you know what it's telling you.

What's Next

The conversation established that executive function is trainable (meta-analyses show small to medium effect sizes from training programs), but did not specify WHAT those training programs involve or HOW the client might systematically build executive function capacity over time. The expert mentioned 'building tomorrow's capabilities' but left the specific methods unexplored, creating natural curiosity about whether there are evidence-based exercises, cognitive training protocols, or lifestyle interventions that could increase baseline working memory or decision-making stamina.

Comments

Leave a Comment