They said everything was fine. Right up until they handed in their notice.

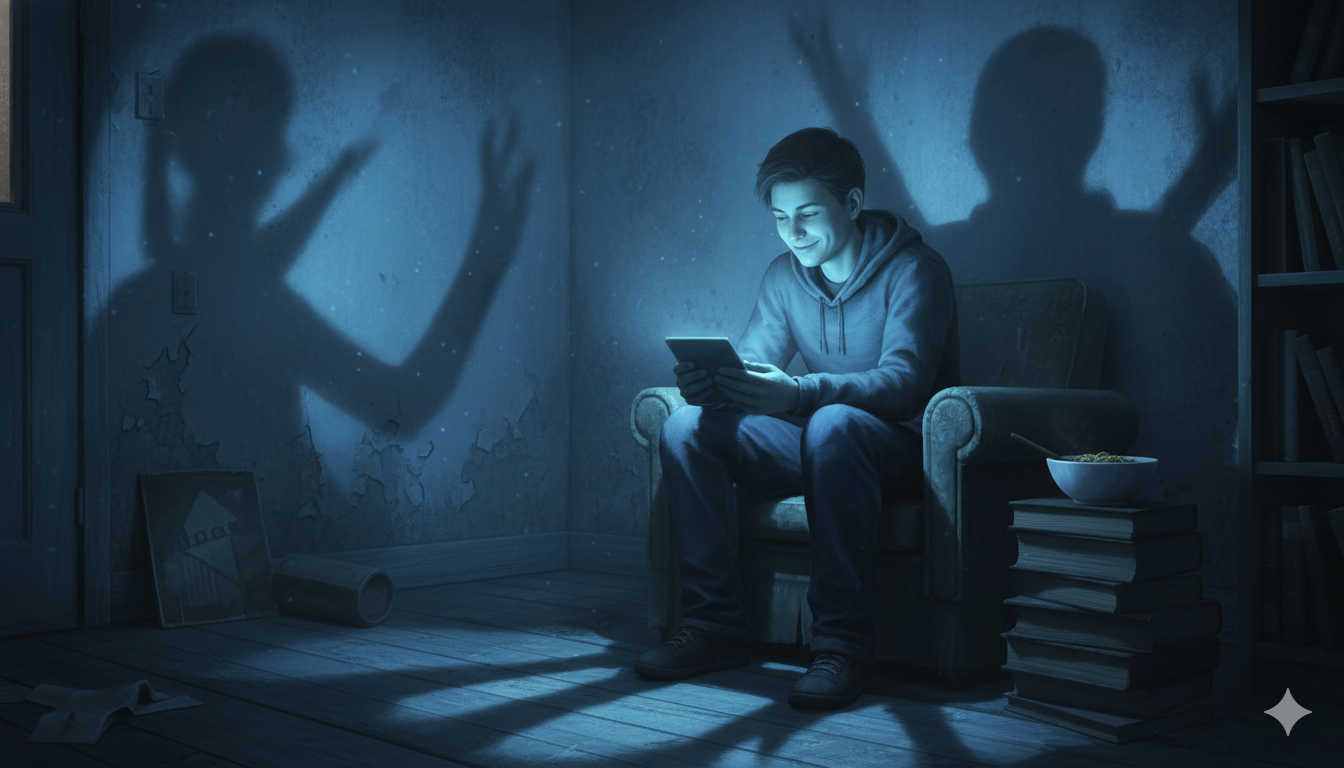

Pam's resignation letter sat in her manager's inbox like a grenade. He had no idea. They had regular one-to-ones. He'd told her his door was always open. She'd never said a word about being unhappy. Three days earlier, she'd deleted an email she'd drafted — just five words: "I'm feeling overwhelmed at work." Not because she didn't trust him. But because she didn't trust what would happen next.

If you're a business owner trying to build a culture where people actually share when they're struggling, you've probably read the standard advice: practice active listening, validate feelings, create safe spaces. These techniques matter. But after 27 years of clinical practice, I can tell you they're not enough—and relying on them alone might be why your staff still aren't talking.

Here's what the research actually shows, and what you can do about it.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Trust

The 2024 APA Work in America survey found that workers with higher psychological safety were dramatically less likely to feel stressed during the workday—27% versus 61%. That's a significant gap. But here's what often gets missed: psychological safety and stress disclosure aren't the same thing.

Psychological safety, as pioneered by Harvard's Amy Edmondson, is about interpersonal risk-taking at work—asking questions, admitting mistakes, proposing ideas that might fail. It's about the work, not about revealing your emotional state.

When we expect employees to disclose personal stress to their managers, we're asking for something different. Something harder. And the power dynamics make it fundamentally problematic.

Think about it: the person you're asking to be vulnerable with is the same person who writes your performance review, influences your promotion, and decides who gets the good projects. Learning active listening doesn't change that structural reality.

A Dutch study on mental health disclosure found that only about 60% of workers who experienced mental health issues disclosed to their managers. The most significant factor wasn't the manager's listening skills—it was whether the worker already had a strong relationship with the manager, and whether they saw potential benefit to disclosing.

Key Insight

Techniques maintain trust that's already been built. They don't create it.

The Three Types of Safety (And Why They're Different)

Most workplace wellbeing advice conflates three distinct things:

1. Operational Safety

"I can raise work problems without being punished." This is what Edmondson's research primarily covers. It's about being able to say "this deadline is unrealistic" or "I made an error on the report" without fear of retaliation.

2. Emotional Safety

"I can express how I'm feeling without judgment." This goes beyond work problems to the emotional experience of work. It's the difference between "this project is challenging" and "I'm anxious and not sleeping well."

3. Vulnerability Safety

"I can admit weakness without career consequences." This is the hardest to create because it requires people to believe that showing struggle won't be held against them—even subtly, even unconsciously—when opportunities arise.

The standard advice about active listening and validation assumes you can technique your way from operational safety to vulnerability safety. The evidence suggests otherwise.

What the Neuroscience Tells Us

Stephen Porges's polyvagal theory introduces the concept of "neuroception"—our nervous system's unconscious scanning for safety or threat. This happens below conscious awareness, through facial expressions, tone of voice, and body posture.

Here's why this matters for business owners: if safety is detected unconsciously, then performing safety through learned techniques will be less convincing than being safe. The autonomic nervous system isn't fooled by someone who learned reflective listening but is actually stressed, distracted, or evaluating you.

What creates genuine safety signals:

- Predictability—the nervous system calms when it knows what to expect. Consistent behaviour, reliable follow-through, clear expectations.

- Co-regulation—calm nervous systems calm other nervous systems. A manager who is genuinely regulated (not performing calm) helps others regulate.

- Reduced threat cues—physical environment matters. Private space for conversations, not glass offices. Body language that's open, not crossed arms and furrowed brows.

The structural interventions we'll discuss next reduce threat at the system level. They don't require anyone to perform safety—they make the environment actually be safer.

A Different Approach: Structure Over Technique

If techniques alone can't create the trust needed for stress disclosure, what can? The answer lies in building systems that don't require emotional vulnerability to function.

Separate Detection from Disclosure

Instead of waiting for people to tell you they're struggling, create anonymous pulse surveys that focus on work conditions, not feelings:

- "My workload in the past two weeks has been: manageable / stretched / unsustainable"

- "I have the resources I need to do my job: yes / partially / no"

- "I know where to go if I need support: yes / no"

Run these weekly or bi-weekly. Aggregate at team level. Managers see trends, not individuals. This gets you signal without requiring anyone to be vulnerable.

Build Automatic Circuit Breakers

Don't wait for disclosure. Build policies that activate based on observable patterns:

- Caps on consecutive high-intensity periods

- Required rest after major deliverables

- Proactive check-ins triggered by changed patterns (missed deadlines, late-night emails, disengagement in meetings)

Separate Support from Evaluation

The person who assesses your performance should not be the primary person you go to for support. This isn't about undermining manager relationships—it's about recognising that the dual role creates an inherent tension.

Options include:

- Peer support networks with trained mental health first aiders

- Skip-level relationships (regular access to your manager's manager)

- External coaching or EAP services with real integration into work context

- HR business partners who are structurally independent

Model Vulnerability from the Top—With Action, Not Just Words

Research from Bell Canada and Unilever found that when senior leaders publicly shared their own mental health experiences, disclosure rates across the organisation increased. But there's a crucial nuance here.

Share struggles that are resolved or being managed, not active crises. "I've dealt with anxiety and here's what I learned" is helpful. "I'm currently drowning and don't know what to do" creates alarm rather than permission.

More importantly, back it up with visible action:

- Executives taking visible mental health days

- Publicly adjusting timelines when stress signals emerge

- Promoting people who asked for help rather than those who hid their struggles

The Question You Should Be Asking Instead

"How are you feeling?" asks for emotional self-disclosure. It puts the burden on the employee to reveal something personal.

"What do you need from me?" asks for operational input. The employee might say "I need the deadline moved" or "I need help prioritising these three projects." They don't have to say "I'm anxious and barely coping."

The difference is between vulnerability and agency. "Here's what I need" is an assertion of what would help. "Here's how I'm struggling" is exposure of weakness.

Some people will choose to share more. That's fine. But they don't have to in order to get support.

Key Insight

You can get people the help they need without requiring them to be emotionally exposed.

Where Listening Techniques Actually Matter

I'm not saying active listening and validation are useless. They matter—for relationship maintenance. The manager who responds well when someone does choose to share is valuable. But the techniques are downstream of trust, not upstream.

What builds trust is the 18 months before that disclosure where you:

- Consistently delivered on promises

- Protected people from political nonsense

- Gave good opportunities even after mistakes

- Showed your own humanity without performing it

- Responded to workload concerns with actual adjustments

You can't technique your way into trust. But once trust exists, good technique helps you honour it.

What to Measure

Don't measure "do people feel safe"—that's self-report that correlates with everything else and tells you little.

Measure:

- Retention rates, especially among high performers

- Sick day patterns (increases often precede burnout)

- Engagement with EAP and support resources (is anyone actually using them?)

- Voluntary turnover reasons in exit interviews

- Time-to-recovery after intense work periods

These tell you whether your systems are actually working, not whether people say the right things in surveys.

The Bottom Line

The standard advice about helping staff share their stress isn't wrong—it's incomplete. Active listening, validation, and non-judgment are valuable skills. But they're maintenance tools for relationships, not construction tools.

If you want people to actually tell you when they're struggling, you need:

- Structural changes that reduce threat at the system level

- Detection methods that don't require emotional disclosure

- Support pathways separate from evaluation relationships

- Consistent behaviour over time that proves trust is warranted

- Questions that invite agency, not just vulnerability

Pam eventually did send that email. Not because her manager had perfect listening skills, but because over two years, she'd seen what happened when others spoke up—and it was good. That's what you're building toward.

The techniques help. But the structure is what makes them work.

Comments

Leave a Comment