It's 3:17am. You're scrolling through your phone, reading nothing in particular, watching videos you won't remember tomorrow. You know you should be asleep. You have a brutal day ahead—doctor's appointments to coordinate, work deadlines you're already behind on, a parent who needs you for everything from medication management to emotional support.

But you can't make yourself put the phone down.

And somewhere in the back of your mind, a familiar voice whispers: What is wrong with you? You complain about having no time, and here you are wasting it. If you were more disciplined, more organized, you could handle all of this.

That voice is lying to you.

The Self-Blame Mistake That's Hurting Your Sanity

When caregivers hit the wall—when work starts slipping, relationships strain under the distance, and exhaustion becomes a permanent state—the natural assumption is that something is wrong with them.

Not enough discipline. Poor time management. Failure to prioritize.

So they try harder. Wake up earlier. Make more lists. Promise themselves they'll be more organized, more efficient, more... superhuman.

But here's what's strange: if poor discipline were actually the problem, trying harder should fix it. More effort should produce more results.

So why doesn't it?

Why does saying yes to everything lead to more missed deadlines, not fewer? Why does refusing to ask for help lead to worse outcomes, not better control? Why does staying up until 3am feel impossible to stop, even when you know it's destroying your next day?

Because discipline isn't the problem. Something else is driving the bus. And until you see what it actually is, you'll keep solving for the wrong variable.

The Truth About What's Really Driving Your 'Yes'

Consider this scenario: You're managing your mother's care after her hospital discharge. Working remotely from her home. Your ex-partner and son are visiting from another country—simultaneously wonderful (you get to see your child) and stressful (navigating a complicated co-parenting dynamic). Your spouse is in a different city. Work is piling up.

And somewhere in the chaos, you have a thought: I wish this visit had been cancelled.

Not because you don't love your son. The time with him is genuinely good. But the timing—layered on top of everything else—is crushing.

Now, what happens next?

For most caregivers, a wave of guilt crashes in. What kind of parent wishes their child's visit was cancelled? What's wrong with me?

But wait. Did you cancel the visit? No. Did you neglect your son? No. Were you present, engaged, showing up despite the overwhelm? Yes.

You didn't do anything wrong. You had a thought—a private, honest acknowledgment that you're overwhelmed.

And yet that thought generates real guilt. Guilt that will influence your next decisions. Guilt that will make you say yes to something else you can't handle, to prove you're not the terrible person your thought supposedly revealed.

This is the hidden driver: guilt is making your decisions, not genuine necessity.

Research on caregiver psychology has identified multiple dimensions of this guilt: guilt about not doing enough for the care recipient, guilt about self-care, guilt about neglecting other family members, and—critically—guilt about having negative feelings at all. Studies show that higher guilt scores correlate significantly with depression, anxiety, and burnout.

The guilt isn't protecting your relationships. It's driving you toward promises you can't keep, which damages those relationships more than an honest "I can't right now" ever would.

Why Your 3am Scrolling Feels Impossible to Stop

Let's return to those late nights. The scrolling, the videos, the "wasted" time.

Here's a question that changes everything: When does the day belong to you?

Not to your mother's medical needs. Not to your employer's deadlines. Not to maintaining a long-distance marriage. Not to managing a visiting ex-partner. When is it just... yours?

For many caregivers, the honest answer is: never.

Every waking hour is claimed by obligation. Someone needs something. Something is urgent. There's always a fire to put out, a ball to keep in the air.

So when does the day finally become yours?

At 3am. When everyone is asleep. When no one expects anything. When—for a few hours—you can do whatever you want, even if "whatever you want" is mindlessly scrolling through content you'll forget immediately.

Psychologists have a name for this: revenge bedtime procrastination.

It's not laziness. It's not poor discipline. It's your psyche fighting for autonomy.

Research shows this is a predictable response when people feel their daytime hours are completely controlled by external demands. High bedtime procrastinators in one study spent an average of 79.5 minutes on their phones before bed, compared to 17.6 minutes for low procrastinators. And they reported more depression and anxiety symptoms, lower sleep quality, and higher insomnia risk.

The behavior makes things worse—everyone knows that. But here's the insight: your mind is correctly identifying a real problem. It's just solving it in a way that backfires.

You genuinely have no time for yourself. Your mind's solution—steal it from sleep—is understandable. But unsustainable.

Stop Trying to Be Superhuman - Here's What Happens When You Do

There's a belief running underneath all of this. It rarely gets spoken aloud, but it drives everything:

I should be able to handle this.

If I were better organized. If I were more disciplined. If I tried harder. If I were... enough.

But there's a problem with this belief. Other caregivers don't manage all of this alone. Other employees say no to unrealistic deadlines. Other people ask for help.

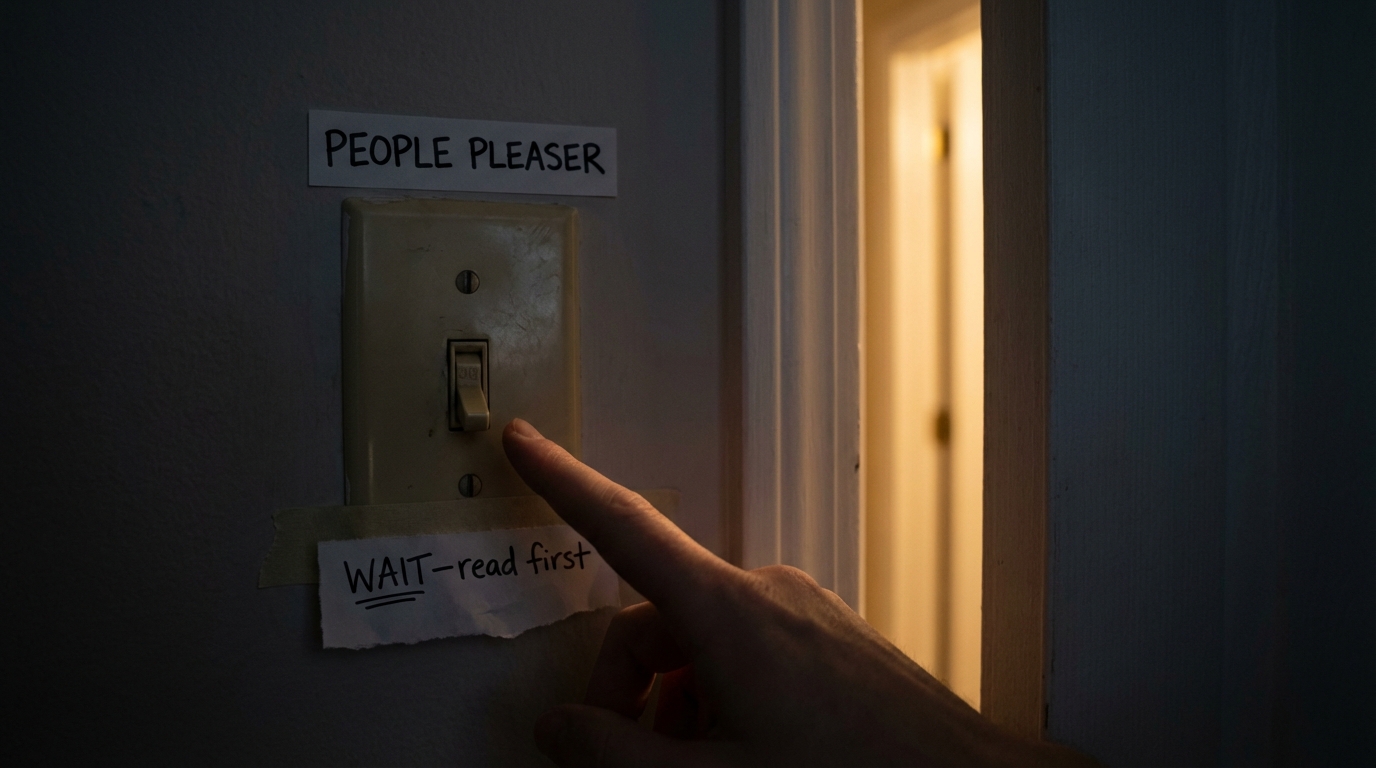

So what's actually underneath "I can't say no" or "I can't ask for help"?

Usually, it's this: Asking for help means I'm failing. Setting limits means I'm letting people down. Having capacity limits means something is wrong with me.

Here's the reframe that changes everything:

You're not failing at being superhuman. You're succeeding at being human—and then punishing yourself for it.

The guilt you feel about wanting rest, about wishing the timing was better, about not handling everything perfectly—none of that guilt is connected to actual harm you've caused. It's guilt about having limits.

And when guilt about having limits drives your decisions, it creates a vicious cycle:

- Fear of disappointing others leads to over-promising

- Over-promising leads to under-delivery (because the promises were unrealistic)

- Under-delivery generates more guilt

- More guilt drives more over-promising

- Repeat until burnout

Research on workplace stress confirms this pattern: overcommitment mediates the relationship between perfectionism and burnout. The fear of letting people down doesn't make you more reliable. It makes you less reliable, because you commit to things you can't deliver.

The Secret to Feeling Less Overwhelmed

Here's something counterintuitive from the research on time management: the primary benefit of tracking your time isn't finding ways to be more productive.

It's psychological.

Studies show that time management is more strongly related to wellbeing than to job performance. The act of seeing where your time goes—even if you don't change much—shifts you from feeling like time is happening to you toward feeling like you have some control over it.

Right now, you probably feel like you're drowning because you don't know how deep the water is. If you could see it clearly, even if it's deep, at least you'd know what you're dealing with.

The fog of overwhelm is often worse than the reality of overwhelm. Visibility is power.

How to Start Taking Back Control Step by Step

The path forward isn't trying harder. It's seeing clearly.

First, get the data. For three days, track where every hour goes. Not to judge it—just to see it. You work with data in other areas of life. You'd never try to optimize a system without understanding how it currently operates. Why would you manage your time without knowing where it goes?

Second, interrupt the guilt pattern. When you notice guilt pushing you toward a decision—saying yes to something, refusing to ask for help, committing to an unrealistic deadline—pause and ask one question:

Is this guilt responding to harm I've caused, or to limits I have?

That single question can break the automatic pattern. Guilt about causing harm is useful information. Guilt about being human is just noise.

Third, recognize the autonomy problem. Those 3am hours represent a real need—time that belongs to you. The solution isn't more discipline to force yourself to sleep. It's finding ways to reclaim personal time during waking hours so your psyche doesn't have to steal it from sleep.

This might mean delegating something. Yes, it takes time upfront to explain. But every task you don't delegate is a task you'll do forever. That's a choice, even when it doesn't feel like one.

It might mean saying no to something and accepting the momentary discomfort of disappointing someone—rather than the larger damage of promising something you can't deliver.

What's the Best Way to Tell Real Duty From Guilt?

Once you can see where your time actually goes, a harder question emerges:

How do you distinguish what's genuinely necessary from what guilt has convinced you is necessary?

Some of your commitments are real. Some are illusions created by a guilt that's lost connection to actual harm. Learning to tell the difference—that's the next layer.

Because when loyalty and guilt masquerade as necessity, you end up serving obligations that aren't as fixed as they feel. And the first step to reclaiming your time isn't finding more hours.

It's finding out how many of the claims on your hours are real—and how many are just guilt wearing a disguise.

Comments

Leave a Comment