You've been doing everything right. Tracking your triggers. Understanding your patterns. Showing up to sessions. Doing the homework.

And then—out of nowhere—a massive anxiety attack hits you in the middle of the week.

Not a small one. The kind that makes you grip the edge of your desk and wonder if you can make it through the next hour.

And the thought that follows is almost worse than the attack itself:

I'm failing. Nothing's actually changing. What's the point of all this work if I'm still having these?

If that thought has crossed your mind recently, I need to tell you something that might sound strange at first:

That anxiety attack might be one of the clearest signs your therapy is working.

The 'Feeling Better' Trap

Somewhere along the way, most of us picked up an idea about healing that seems obviously true:

If therapy is working, you should feel better. Fewer panic attacks. Smaller emotional reactions. A general upward trend.

So when the opposite happens—when you've been doing the work and suddenly you're hit with an anxiety attack that feels like proof of failure—the conclusion seems inescapable: something's wrong. The treatment isn't working. You're back at square one.

But here's where that logic breaks down.

Think about the last time you had a breakthrough in therapy. Not a small insight, but a real shift—the kind where something that had been gripping you for years suddenly loosened.

How did you feel during that session? Before the shift happened?

If you're like most people doing trauma work, the answer isn't "calm and comfortable." It's closer to terrible. Raw. Like everything was more intense than usual, not less.

The breakthrough didn't happen despite feeling awful. The breakthrough happened because you were willing to feel it.

What Happens When You Feel Worse

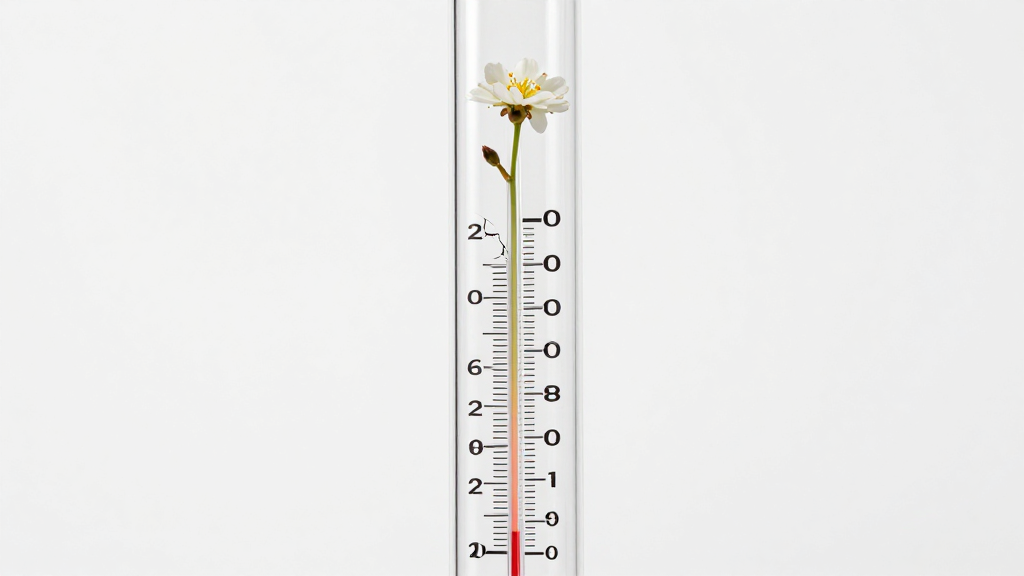

Here's something that isn't talked about enough: temporary symptom increases during trauma therapy are not just normal—they're expected.

Studies on prolonged exposure therapy consistently find that people often feel worse before they feel better. Their anxiety might spike. Old memories might surface at inconvenient times. The emotional temperature rises.

And here's the part that surprises most people: this symptom spike does not predict poor outcomes.

Research shows no indication that these temporary increases harm the healing process. Patients who experience symptom worsening during treatment still show significant improvement over time.

The discomfort isn't a sign you should stop. The discomfort is the work.

Think about it this way: You can't clean out a closet without first making a mess. The stuff that's been shoved in there for years has to come out before it can be organized. And while it's out, your room looks worse than when you started.

Trauma therapy works the same way. When you start opening doors that have been locked for years, you don't get to choose when the contents come spilling out.

Why Avoidance Keeps You Stuck

This brings us to something that might hit closer to home.

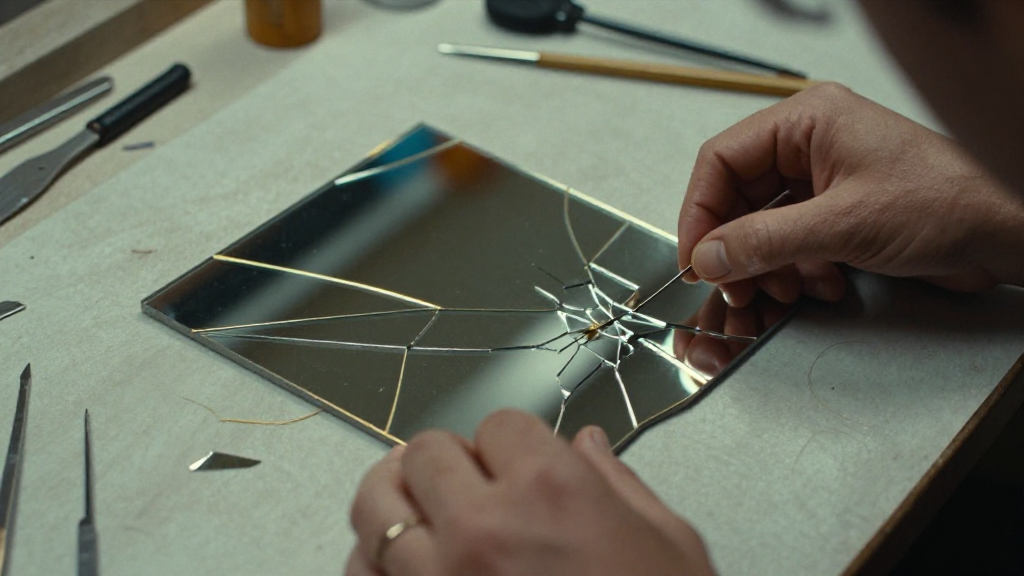

When painful things happen—especially when we're young—we learn to protect ourselves. We build walls. We avoid certain topics, certain people, certain places. Maybe even entire cultures.

And for a while, it works. The avoidance keeps the pain at bay.

But here's what nobody tells you: that locked door you built to keep the pain out? Over time, it starts keeping the pain in.

The things you won't touch, won't listen to, won't visit—they don't fade with distance. They stay frozen exactly as they were, waiting. And every encounter with something that reminds you of them triggers the same response you had years ago.

You haven't moved past it. You've been walking around it.

This is why exposure therapy works—and why it feels so counterintuitive. The path forward goes through the discomfort, not around it.

About 25-30% of people find exposure therapy uncomfortable enough to consider stopping. That's real. The distress isn't imagined. But the research is clear: that discomfort doesn't mean the treatment is failing. It often means you're finally accessing material that's been locked away, waiting to be processed.

The Native Language Secret Nobody Talks About

There's one more piece to this that most people never hear about.

If you experienced difficult things in childhood—especially if those experiences happened in a language different from the one you use in daily life now—there's a mechanism at work that explains a lot.

Trauma memories don't just store the content of what happened. They store the context. The sensory details. And critically: the language.

Research on bilingual emotional processing has found something remarkable: traumatic memories are more strongly connected to distress when processed in the language they were encoded in.

Your native language—the one you spoke when the difficult things happened—unlocks deeper emotional access than a language you learned later. This isn't a flaw. It's actually how healing works.

Speaking about painful memories in your second language can feel safer. More distant. Easier to manage. But that distance comes at a cost: you might not be accessing the full emotional weight of the memory.

To fully process what happened, you often need to go back to the language it happened in. That's where the feelings are stored.

This explains why certain triggers hit differently. Why some conversations feel manageable and others knock you sideways. The pathway to the deepest wounds often runs through the language you've been avoiding.

How to Read Your Symptoms Differently

If you've been in therapy and experiencing more distress lately—not less—consider the possibility that this isn't regression.

You're not back at square one. You're finally reaching square one.

The anxiety attacks, the raw emotions, the memories surfacing at odd moments—these may be signs that you're accessing material that has been sealed away, sometimes for decades. And while it doesn't feel like progress, it often is.

The measure of healing isn't whether you feel comfortable. It's whether you're willing to feel what you've been avoiding.

When that email from a colleague triggers something that feels way too big for the situation—that's not you being oversensitive. That's an old wound getting activated. The fact that you can recognize it now, even while it's happening, represents a kind of awareness that wasn't available before.

When doing exposure exercises makes you feel worse before you feel better—that's not the therapy failing. That's exactly what the research predicts. Temporary increases. Followed by lasting reductions.

When engaging with things you've avoided for years—music, places, even language itself—brings up waves of emotion, that's not a sign you should retreat. It might be the first step toward reclaiming parts of yourself that the pain had taken hostage.

How to Move Forward Without Forcing It

So what do you do with this?

First, stop interpreting every spike in anxiety as evidence of failure. The spike might be evidence of engagement.

Second, notice what you've been avoiding—and consider whether that avoidance has been keeping you stuck rather than keeping you safe. The things that trigger you most might be exactly what needs your attention.

Third, if there's a language or cultural context connected to your early experiences that you've been steering clear of, that avoidance might be worth examining. Not because you need to force yourself into overwhelming exposure, but because gradual, intentional contact with those avoided elements can be part of the healing process.

The goal isn't to stop feeling connected to where you came from. It's to process the difficult parts so that connection doesn't automatically mean pain.

You can love what you come from without being destroyed by what happened there.

But getting there requires going through the raw part first. And if you're in the raw part right now—that 70-point reduction waiting on the other side? It's real. And the fact that you feel terrible might be the clearest sign that you're finally doing what needs to be done.

What Comes Next

Once you understand that symptom spikes are part of the process—not proof of failure—a new question emerges:

What makes certain triggers hit so hard in the first place?

Why does a rude email from a colleague activate the same feelings you had as a child? Why do some interactions feel like minor annoyances while others feel like threats to your core?

Understanding the anatomy of these triggers—why some beliefs cut so deep and how they got installed in the first place—opens up new possibilities for responding differently when they get activated.

That's worth exploring next.

Comments

Leave a Comment