Ready to Stop Checking Your Body for Symptoms? Here's How

You feel a sensation in your throat-nothing dramatic, just... something. Within seconds, your hand is moving toward your neck. You're checking. Pressing. Feeling for lumps, for changes, for anything that might signal danger.

Five minutes pass. Sometimes ten. You tell yourself you're being responsible, that catching something early could save your life. But here's what troubles you: the relief never lasts. Tomorrow, or maybe even an hour from now, you'll feel that urge again. The anxiety returns, and with it, the need to check.

If checking gave you lasting peace, you'd check once and be done. But it doesn't work that way. And that pattern-the one where the solution seems to make the problem worse-is actually revealing something important about what's happening beneath the surface.

What Your Brain Learns When You Check

When you check your throat and the anxiety drops (even temporarily), something significant happens in your brain. You're not just relieving anxiety in that moment-you're teaching your brain a very specific equation:

Anxiety + Checking = Relief

Here's the critical question: does checking your throat actually change whether something medically concerning is happening in your body?

The answer, of course, is no. If something were developing, checking wouldn't make it appear or disappear. But your brain isn't processing it that way. When you check and find nothing, your brain doesn't conclude "I'm healthy." It concludes "Checking kept me safe."

This is what researchers call a safety behavior-an action performed in response to anxiety rather than actual symptoms. And safety behaviors have a paradoxical effect: they provide immediate relief while strengthening the anxiety over time.

Studies on health anxiety show that checking and reassurance-seeking maintain anxiety through what's called negative reinforcement. Each time you check and feel temporarily better, you're reinforcing the belief that checking is necessary for safety. The behavior that feels like the solution is actually preventing you from discovering the truth: that you're safe without checking.

Why the Urge to Check Gets Stronger Over Time

Every time you complete the cycle-feel anxious, check, feel relieved-something physical changes in your brain. The neural pathway connecting "anxiety feeling" to "checking behavior" to "relief" gets stronger.

Think of it like a path through a forest. The first time you walk it, you're pushing through undergrowth, moving slowly. But walk that same path daily, and it becomes cleared. Then worn. Then a dirt path. Eventually, with enough repetition, it becomes a paved road you can travel without thinking.

This is neuroplasticity at work-your brain's ability to strengthen connections that get used repeatedly. It's the same mechanism that allows you to learn any skill. But in this case, you're becoming skilled at anxiety-driven checking.

The pathway gets so automatic that you might find your hand moving to your throat before you're even consciously aware of feeling anxious. The urge feels overwhelming because you've built a superhighway connecting threat perception to checking behavior.

This explains something that probably troubles you: why checking seems to be getting more frequent, not less. Why the urge feels stronger over time rather than weaker. You're not getting sicker or more anxious-you're getting more practiced at the checking response.

The Truth About Your Checking Behavior

Now here's where we need to get curious about what's really driving this pattern.

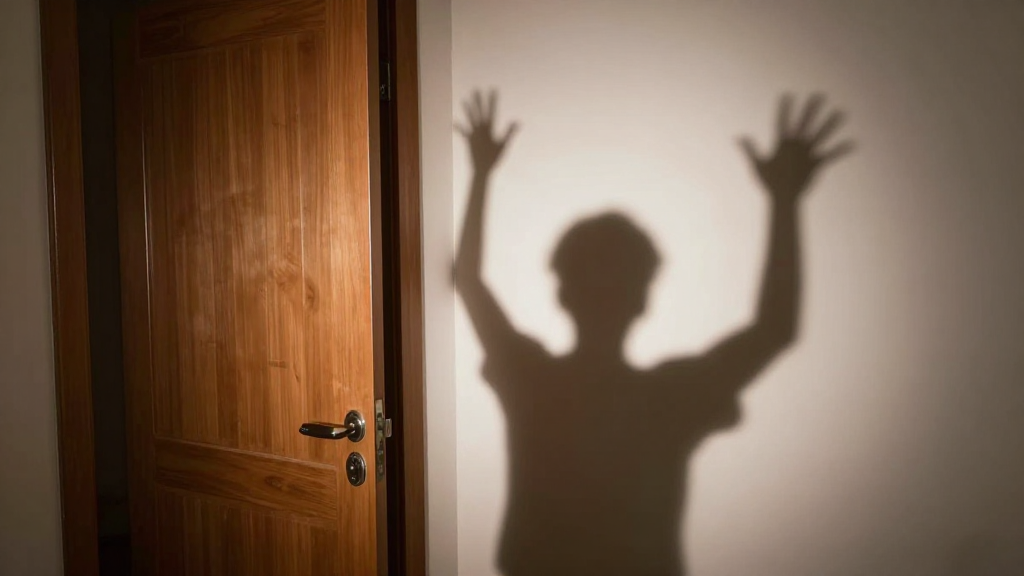

You lost your mother when you were nine years old. That experience taught your nervous system something devastating: that safety can disappear without warning. That mothers-the primary source of security-can suddenly be gone.

Now you have a daughter, Eva. And the thought that haunts you isn't just about dying-it's about her experiencing what you experienced. The terror and confusion of losing a mother. Being left without the one person who understands her.

Your checking behavior isn't random. It's not weakness, and it's not you being "too anxious." It's your brain running a protection program that was installed when you were nine: scan constantly for danger, because safety disappeared once without warning.

Research on early parental loss shows lasting effects on threat detection systems. When children experience the death of a parent, their nervous systems often become more sensitive to threat-related information. The amygdala-the brain's alarm center-develops with a lower threshold for activation. This isn't pathology. It's your nervous system adapting to an environment where safety was unpredictably compromised.

Your heightened sensitivity to health information, your reaction to hearing about someone else's cancer diagnosis, your rapid physical response before thoughts even form-these are features of a threat detection system that learned to stay vigilant. Your body reacts before your thinking brain gets involved because that's what protected you (or tried to) when you were young and vulnerable.

So let's be clear: your brain's intention is beautiful. It's trying to prevent Eva from experiencing your trauma. It's trying to keep you alive and present for your daughter.

But here's the distinction that changes everything: your brain's intention is protective, but its method is problematic.

The checking behavior feels like vigilance, like responsible health monitoring. But it's actually maintaining the anxiety it's meant to resolve.

Why Finding Nothing Wrong Doesn't Bring Lasting Relief

Here's what makes this pattern so difficult to escape: when you check and find nothing concerning, your brain attributes your safety to the checking itself.

Imagine you had a button you pressed every day to prevent earthquakes. Each day you press it, no earthquake happens. How certain would you become that the button works? Even though earthquakes are rare regardless of button-pressing, you'd develop an unshakable belief in the button's power.

This is exactly what happens with health checking. Each time you check and find nothing, you're not learning "I'm healthy and illness is unlikely." You're learning "Good thing I checked-that's what kept me safe."

So you need to check again tomorrow. And the next day. And the next. The behavior that was supposed to give you peace becomes the source of ongoing anxiety.

The trap is closed: you can't stop checking because checking is what you believe is keeping you safe.

What's the Difference Between Medical Vigilance and Safety Behaviors?

You might be wondering: isn't it responsible to pay attention to your body? Isn't checking a form of health awareness?

Here's the critical distinction: medical vigilance responds to actual symptoms; safety behaviors respond to anxiety.

Medical vigilance looks like this:

- Noticing a symptom that persists or worsens over days to weeks

- Observing something measurable or visible to others

- Seeking appropriate medical evaluation when symptoms meet concerning criteria

- Symptoms that occur regardless of your anxiety level

Safety behaviors look like this:

- Checking triggered by anxiety rather than new symptoms

- Sensations that fluctuate with stress levels

- Symptoms that intensify when you focus on them and decrease when distracted

- Repetitive checking that provides only temporary relief

You already know the difference. When you're checking your throat for 5-10 minutes multiple times a day, you're managing anxiety, not monitoring health.

How Understanding This Pattern Makes Change Possible

Understanding this mechanism changes what's possible for you.

You're not broken. You're not irrational. You're not "too anxious." You have a highly sensitive threat detection system (shaped by early trauma) that learned an ineffective safety strategy (checking) which accidentally strengthened through neuroplasticity (the superhighway effect).

Every element of this pattern makes sense. And more importantly: if neuroplasticity built these pathways, neuroplasticity can modify them.

The superhighway you've paved-the one connecting anxiety to checking-gets stronger with use. But here's what's equally true: neural pathways weaken with disuse. And alternative pathways can be strengthened.

You're not trying to eliminate anxiety entirely. Some anxiety about health is protective and normal. The question is: how do you help your brain distinguish between useful protective anxiety and the anxiety trap that's keeping you exhausted?

How to Become a Pattern Detective

Change doesn't start with stopping the checking. It starts with seeing the pattern clearly.

For the next week, your only job is to observe. Not to change anything-just to notice. When the urge to check arises, track three things:

1. What triggered it?

- Was it a body sensation you noticed?

- A thought about illness?

- Something external, like hearing about someone else's health problem?

2. How strong is the urge?

- Rate it from 1-10

3. If you check, how long until the urge returns?

- Five minutes? An hour? The next day?

You're gathering data about your personal pattern. You're learning how the equation plays out specifically for you. Does the urge intensity correlate with certain triggers? Is the relief sustained or fleeting? Do certain contexts make the urge stronger?

This observation builds awareness-the foundation for everything else that becomes possible. You're not trying to white-knuckle your way through urges. You're becoming a scientist studying your own nervous system.

And here's what this makes visible: you'll start to see the difference between moments when your body is signaling something worth medical attention versus moments when anxiety is triggering the checking urge.

What Your Anxiety Teaches Your Daughter

There's one more thing worth considering.

Your daughter is watching you navigate anxiety. Right now, if the pattern continues, she's learning that anxiety controls behavior, that vigilance equals safety, that threats lurk everywhere requiring constant checking.

But what if she could watch you navigate anxiety differently? What if she learned that you can feel afraid and still move forward? That anxiety doesn't have to run your life? That you have power even in the face of fear?

You experienced powerlessness at nine when your mother died. But you have power now-the power to teach Eva something different about what anxiety means and how to live with it.

Breaking this pattern isn't just about reducing your distress. It's about rewriting the story of what anxiety means in your family.

Can These Patterns Actually Change?

You asked something important: if your brain built these superhighways after your childhood trauma, can they actually be changed? Or are you stuck with these patterns?

That question-about whether neural pathways shaped by early experience can be modified-is exactly where this gets interesting. Because if checking strengthens certain pathways, then other behaviors must strengthen different pathways. The brain that learned to check compulsively is the same brain that can learn to respond differently.

But that's not where we're starting. We're starting with observation. With seeing the pattern clearly. With understanding what your brain has been trying to do, and why its method hasn't been working.

Your homework this week is simple: notice the three things. Track the pattern. See what becomes visible when you look carefully at what's been happening automatically.

And pay attention to this: when you observe the urge without immediately acting on it, even for a few seconds, you're already beginning to introduce space into a pattern that's been running on autopilot.

That space-between urge and action-is where change becomes possible.

What's Next

Stay tuned for more insights on your journey to wellbeing.

Comments

Leave a Comment