Twelve interviews. Four months. Zero offers.

Twelve interviews. Four months. Zero offers.

You know your technical stuff. You can solve the coding problems. You understand system design. But something keeps going wrong, and you have no idea what it is.

So you've started to believe the only explanation that makes sense: you're just bad at interviews. Maybe you're not cut out for this. Maybe there's something fundamentally wrong with how you come across.

And now you're looking at AI interview prep tools, wondering if they'll help-or if they'll just reinforce whatever invisible mistakes are tanking your chances while your savings evaporate.

Here's what you need to know: the explanation you've settled on is wrong. And that's actually good news.

What Everyone Believes

When interviews fail repeatedly, most people-including you, probably-land on one of two explanations:

Option 1: It's me. I'm bad at interviews. I don't interview well. It's a character flaw, a personality limitation, maybe something about how I'm wired. Some people are good at this, and I'm not.

Option 2: It's random luck. The interviewers were biased. They'd already picked someone internally. The cultural fit wasn't right. It's a numbers game, and I just haven't hit my number yet.

Both of these explanations have something in common: they offer no actionable path forward.

If it's a fundamental character flaw, what can you do? Try harder? Be more confident? You've already tried that. If it's random luck, you just keep rolling the dice and hope the next one lands differently.

So you keep preparing the same way. You practice more interview questions. You try to project confidence. You tell yourself to relax. You maybe read another book on interview techniques.

And the failures continue.

The Crack in the Foundation

Here's what should bother you about the "I'm bad at interviews" explanation:

If you build an FPV drone and it keeps crashing, do you conclude you're "bad at drones"? No. You check the flight controller logs. You test each component. You review the video footage to see exactly when it starts to fail.

You look for the specific malfunction.

But with your interviews, you're not doing that. You're making a global judgment about yourself without any diagnostic data. You're saying "the whole system is broken" when you haven't identified which component is failing.

And here's the question that should crack this whole explanation open: Can you see what interviewers see when they look at you?

Can you observe your own facial expressions? Your posture? Your eye contact patterns? The micro-movements of your hands? The fluctuations in your vocal pitch?

No. You can't. You're inside the experience, not outside it.

Which means you're trying to diagnose a problem using a method that can't possibly reveal it.

The New Truth

Research reveals something most people never consider: interview failures often stem from invisible signals you're sending that you cannot self-observe.

When you're anxious during an interview, your body produces specific nonverbal behaviors-changes in gaze patterns, subtle fidgeting, vocal characteristics, posture shifts. You can't see these behaviors in yourself. But interviewers can see them. And studies show these behaviors significantly lower the competence ratings that interviewers assign to candidates.

Here's the mechanism: observers watch candidates displaying high anxious nonverbal behavior and give them lower interview performance ratings-even when the candidate's actual answers are strong. The anxiety signals act like noise in a transmission. The content (your technical answers) might be perfect, but the delivery mechanism (your nonverbal presentation) degrades how the message is received.

And here's the part that explains why you can't figure this out on your own: interviewers aren't consciously aware that nonverbal anxiety cues are driving their perception.

They don't think, "This candidate is fidgeting, therefore I'm rating them lower." They just experience you as "less competent" and rationalize it afterward. That's why the rejection feedback you get is useless-"we went with another candidate," "cultural fit concerns." The interviewers themselves don't know what drove their negative impression.

You're not bad at interviews. You're sending signals you can't see that trigger judgments interviewers can't articulate.

That's a completely different problem. And it has a completely different solution.

Why the Old Way Never Worked

Now let's trace back through every strategy you've tried and watch them fail for a specific reason.

"I need to practice more interview questions." You thought the problem was not knowing what to say. But research shows that interviewers make their decisions within the first 10 seconds to 15 minutes of an interview-and then spend the rest of the time seeking evidence that confirms that snap judgment. If you've triggered a negative impression in the first moments through anxious nonverbal behavior, nailing the technical questions later doesn't override it. You were fixing the wrong component.

"I need to be more confident." You thought the problem was internal confidence, so you tried to psych yourself up. But confidence is an internal state. The problem is external behavior. You can feel confident and still display anxious nonverbal signals-because you can't see yourself doing it. You were trying to change something invisible to you.

"I need to figure out what I'm doing wrong." You thought introspection would reveal the answer. But psychological research is clear: introspection has severe limits. You cannot access through self-reflection alone how others perceive your nonverbal behavior. The information simply isn't available to your conscious mind. You were using a tool that couldn't reach the problem.

"I need feedback from interviewers." You thought human feedback would diagnose the issue. But interviewers process your anxious nonverbal cues unconsciously. They experience the resulting negative impression as a judgment about your competence, not as a reaction to your anxiety signals. So they give you generic feedback that doesn't identify the actual mechanism. You were asking people who don't know the answer themselves.

Every single strategy failed because they all assumed the problem was something you could access through conventional means.

But the real cause-the specific nonverbal anxiety behaviors you're displaying-operates in your blind spot.

The Element Everyone Missed

Here's what almost no one talks about when they discuss interview preparation: you have a measurement problem, not just a skill problem.

Think about your drone flying. You have multiple measurement systems:

- The FPV camera shows you one perspective

- The flight controller logs show you data you can't feel while flying

- Ground video shows you what observers see

Each measurement system reveals different problems. The logs might show tiny oscillations you can't feel. The ground video might reveal a drift pattern you can't see from your FPV perspective.

You don't try to fly better by thinking harder. You use measurement instruments to see what you can't otherwise observe.

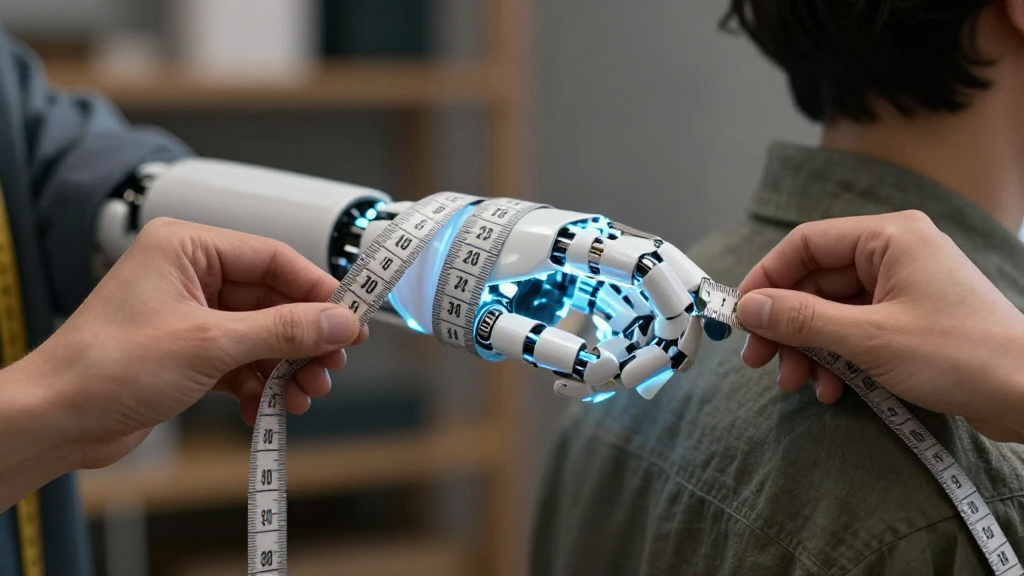

That's the element everyone overlooks with interview preparation: AI interview tools aren't coaches or magic solutions-they're measurement instruments.

A well-designed AI interview tool built on behavioral research can track things you cannot see:

- Eye contact patterns ("You break eye contact within the first 15 seconds when discussing your previous role")

- Fidgeting frequency and timing ("Your hand movements increase 40% when answering behavioral questions")

- Vocal characteristics ("Your speech rate accelerates and your pitch rises during technical explanations")

- Posture changes that correlate with specific question types

These are specific, measurable behaviors. Not vague advice like "be more confident." Actual data about what you're doing that you can't introspect your way to.

Research on AI feedback systems shows they can effectively support behavioral change when they provide specific, objective measurements. Studies in therapeutic contexts demonstrate that AI-generated feedback significantly improves adherence and outcomes-not because the AI is smarter than humans, but because it measures consistently and without the social anxiety that makes human practice uncomfortable.

And here's the forgotten factor that makes AI tools particularly valuable for your situation: they create a judgment-free practice environment.

When you practice with another person, you're anxious about their judgment. That social anxiety interferes with both your performance and your ability to seek feedback. Research on metacognition shows that social factors often prevent people from seeking the help they need, even when they know they have knowledge gaps.

AI tools eliminate that barrier. You can record yourself answering the same question ten times. You can fail spectacularly without embarrassment. You can test whether changing a specific behavior (making eye contact for the first 20 seconds) actually changes the assessment before you try it in a real interview.

You're not replacing human interaction. You're adding a measurement system that reveals what humans-including you-can't consciously observe.

What You Can Now Forget

You can stop carrying these beliefs:

"I'm bad at interviews." This is a global, stable attribution that packages you as fundamentally flawed. It's not true. You have specific behavioral patterns operating in your blind spot. That's fixable.

"If I just try harder or think more carefully about it, I'll figure out what's wrong." Introspection cannot reveal how others perceive your nonverbal behavior. The harder you try to solve this through self-reflection, the more you reinforce learned helplessness. The information isn't accessible that way.

"I need someone to tell me what I'm doing wrong." Human interviewers can't tell you because they don't consciously know. Their negative impressions form below their awareness. Even a coach might not identify the specific anxiety signals because they're processing them unconsciously too.

"This is going to take forever to fix, and I'm running out of time." Once you know the specific behaviors you're displaying, behavioral change can happen relatively quickly. You're not rebuilding your personality. You're modifying measurable patterns. And research shows that addressing interview anxiety doesn't just change your behavior-it actually improves the validity of the interview as an assessment tool, which means you're more likely to be accurately evaluated for your actual capabilities.

Put these burdens down. You've been carrying explanations that don't fit the evidence.

What Replaces It

Here's your new understanding:

You have diagnostic blind spots, not fundamental flaws. The problem isn't your capability or your personality. It's that you cannot observe your own nonverbal behavior during high-stakes situations. This is a universal human limitation, not a personal failing.

External measurement reveals what introspection cannot. Just as flight controller logs show oscillations you can't feel while flying, AI interview tools can measure behavioral patterns that operate below your conscious awareness. The tool isn't smarter than you-it just has a different vantage point.

AI tools are complementary measurement systems, not replacement solutions. You might need human coaching to practice the fixes, but you need the diagnosis first. The AI identifies the specific behaviors ("gaze breaks at 12 seconds," "speech rate increases 40%"), and then you can systematically work on changing them.

You can validate the measurement before trusting it. Record multiple practice interviews and see if the AI identifies consistent patterns-specific behaviors that show up repeatedly, not random noise. Test whether changing those specific behaviors actually changes the AI's assessment. Treat it like an experiment where you're validating the instrument before using its data to make decisions.

The problem is more fixable than you thought. You're not starting from scratch. You're debugging a specific component. And because the problem is specific and measurable, the solution is too.

What Opens Up

Once you see interview preparation as a measurement and diagnosis problem rather than a character flaw:

You can stop the learned helplessness cycle. Repeated failures create helplessness when you attribute them to internal, stable, global causes ("I'm bad at this"). But when you understand the actual mechanism-invisible anxiety signals triggering unconscious interviewer bias-the attribution changes. It's not you. It's a fixable technical problem.

You can practice systematically instead of randomly. Instead of doing more interviews and hoping something changes, you can identify the specific 2-3 behaviors that are triggering negative first impressions, practice modifying them in a safe environment, and validate the changes before your next real interview.

You can rebuild your confidence on evidence. Right now your confidence is eroding because you keep failing without understanding why. But once you identify your specific behavioral patterns and start changing them, you'll have objective evidence of improvement. That's a different kind of confidence-one based on measurement, not hope.

You can convert interviews faster than your last four months suggest. If the problem has been invisible signals in your first impression, fixing those signals could dramatically change your conversion rate. You're not necessarily as far from success as your timeline suggests-you've just been working on the wrong variables.

You can make decisions from clarity instead of desperation. The fear of "having to take any job" comes from feeling out of control. But you're not out of control-you just didn't have the measurement tools to see what was happening. Now you know what to look for.

The path forward is concrete: Record three practice interviews. Run them through an AI tool that provides specific behavioral metrics. Look for consistent, measurable patterns across multiple recordings. Test whether changing those specific behaviors changes the assessment. Then take that validated insight into your next real interview.

You're not bad at interviews. You've been flying blind.

Now you know how to turn on the instruments.

What's Next

In our next piece, we'll explore how to apply these insights to your specific situation.

Comments

Leave a Comment