When Being Productive Is Actually Avoidance

You're doing everything right.

You passed your Royal Horticultural Society exam. You're volunteering at the garden. You started yoga classes with strangers. You're taking mindfulness walks, practicing meditation daily, even sitting through cancer-related content despite the panic it triggers.

From the outside, you're facing your fears and building a life.

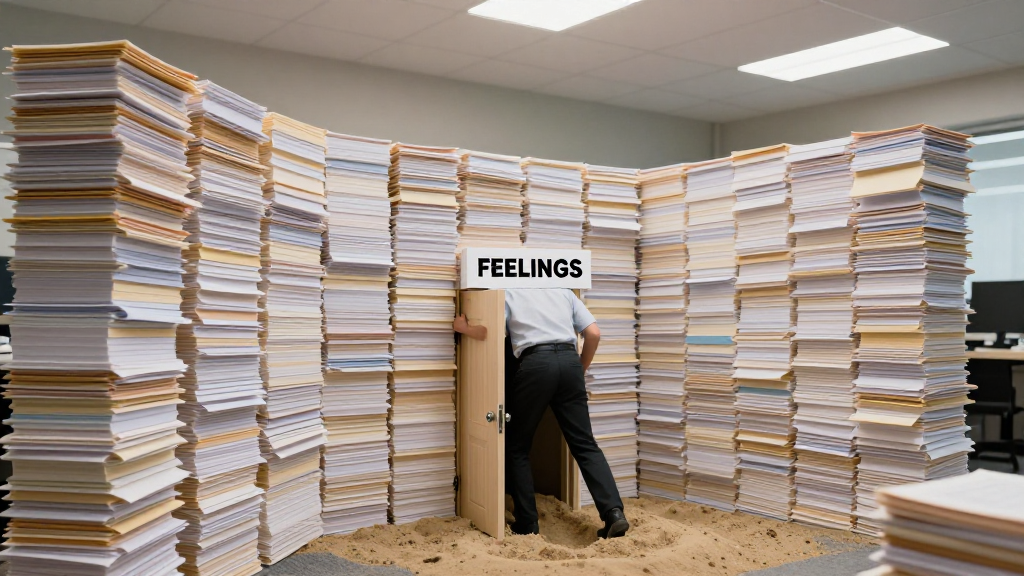

But here's what you've started noticing: even when you're doing something productive, something positive, it doesn't quite feel like choosing to be there. It feels like running from something else. Like staying busy enough that you don't have to be alone with your thoughts.

And the avoidance patterns you know must exist? They've become so automatic, so "second nature," that you can't even see them anymore.

The Pattern You Can't See

In your gardening work, you know exactly what happens when a plant becomes root-bound. The roots grow in tight circles inside the container. And here's the strange part: even when you transplant that plant into open soil with room to spread, the roots keep growing in the same circling pattern. They've trained themselves into that shape.

The space for growth is there. But the plant doesn't use it.

Your avoidance patterns work the same way. They formed during a time when they protected you—when avoiding certain thoughts, situations, or feelings genuinely kept you safer. But now, even though circumstances have changed, the patterns continue automatically. You keep circling in the same protective shape, even when there's room to grow differently.

The Mistake Everyone Makes About Anxiety

When anxiety shows up—the racing heart, shallow breathing, that sinking feeling in your stomach, the nausea—most people identify those symptoms as the enemy. The problem to solve. The thing that needs fixing.

So they try the logical solutions: deep breathing to calm the body down, positive self-talk to override the fear, staying busy to avoid triggering situations, or gradually exposing themselves to feared scenarios while white-knuckling through the discomfort.

You've probably tried versions of all of these. And some of them have helped, at least partially. You did manage to sit through cancer-related content. You are attending yoga classes with strangers. You are volunteering despite the anxiety.

But there's still something missing. The anxiety keeps returning. The patterns stay invisible. And even your successes feel more like escaping one fear by facing a different, slightly less terrifying one.

What Your Motivation Reveals

Here's what reveals the real problem: You attend volunteer gardening because your fear of ruminating alone outweighs your discomfort with being around people.

Read that again.

You're not choosing to volunteer because you want to be there. You're choosing it because you're fleeing something else.

This is the distinction most people miss: avoidance doesn't just mean staying home in bed. It includes staying extremely busy. Helping others to the point of self-neglect. Engaging in one activity specifically to not do another. Even positive, productive behaviors can be forms of avoidance.

And here's what research on anxiety and avoidance has discovered: Every time you avoid something, you're not just removing yourself from discomfort. You're teaching your brain that the avoided thing truly is dangerous.

How Your Brain Records Danger

Think of your brain as keeping a running journal of threats. Every time you encounter something and then avoid it, your brain makes an entry: "Confirmed dangerous. Avoidance necessary for survival."

The more you avoid, the more entries accumulate. The threat assessment gets stronger. The avoidance feels more justified, more automatic, more necessary.

This is why your avoidance patterns have become "second nature"—invisible to you now. They're deeply practiced responses that your brain executes automatically, without conscious thought, because they've been reinforced thousands of times.

It's also why even productive activities can be problematic when they're motivated by avoidance. You're not teaching your brain "being around people is safe" when you volunteer. You're teaching it "being alone with my thoughts is so dangerous that I must flee to other people."

The threat signal gets reinforced either way.

What Happens When You Stay With Discomfort

But you've already discovered something that changes everything. You just might not have realized how significant it is.

When you sat through cancer-related content, you experienced something specific: "The physical symptoms were intense at first—heart racing, that sinking feeling in my stomach, shallow breathing. But then... they just started fading after a few minutes. It surprised me that they didn't keep building."

That experience reveals an invisible process happening in your nervous system. It's called habituation.

Here's how it works: When you stay with uncomfortable stimuli without escaping—when you don't avoid, don't distract, don't flee—your nervous system runs a test. It keeps the alarm active for a period of time, monitoring for actual danger.

And when no actual danger appears? When the feared catastrophe doesn't happen? Your nervous system starts turning down the alarm. The threat assessment weakens. The physical symptoms peak, then naturally subside.

You experienced this firsthand. Your anxiety didn't keep building infinitely. It peaked, then faded—all on its own, without you having to fight it or fix it.

Your nervous system was learning: "This situation feels threatening, but it's actually safe."

How Graduated Exposure Rewrites Threat Signals

In gardening, you know the process of hardening off seedlings. You can't just move them from indoor protection to full outdoor exposure—they'd go into shock. Instead, you gradually expose them to outdoor conditions. A little longer each day. Slightly more wind, more direct sun, cooler temperatures.

The gradual exposure doesn't just help them tolerate the conditions. It actually makes them stronger. More resilient. Better equipped to thrive.

Your nervous system works the same way.

Graduated exposure to feared situations—staying with the discomfort long enough for habituation to occur—doesn't just reduce anxiety. It rewrites the threat journal. It teaches your brain new entries: "Thought this was dangerous. Stayed with it. Nothing bad happened. Adjusting threat level down."

But here's the critical piece most people miss: This learning only happens when you stay with the discomfort without using safety behaviors.

Safety behaviors are the subtle ways you protect yourself while technically "facing your fear." Like being physically present in social situations but keeping conversations surface-level. Sharing gardening achievements with friends but not struggles. Showing up for activities but not being fully present emotionally.

You described it perfectly: "I'm present but not fully present."

When you use safety behaviors, your nervous system doesn't get the full data it needs. You're essentially telling your brain: "Yes, I'm in this situation, but I'm protecting myself because it is still dangerous." The threat level stays high.

Why Self-Compassion Makes Exposure Work Better

Here's where most people get it backwards.

You mentioned worrying that being kind to yourself during difficult moments was "somehow letting yourself off the hook or not pushing hard enough." This reflects the common belief that you need to be tough on yourself, discipline yourself, force yourself through discomfort.

But research on exposure therapy has found something surprising: Self-compassion during exposure exercises actually increases effectiveness.

Studies show that people who are harsh with themselves during anxiety-provoking situations are less likely to continue exposure work. The internal criticism becomes another threat, another source of discomfort to avoid. They start avoiding the exposure itself.

But people who practice gentle self-redirection—who acknowledge the difficulty without judgment, who remind themselves that anxiety is a normal part of learning—persist longer. They complete more exposures. They achieve better outcomes.

Your gentle approach isn't weakness. It's scientifically optimal.

When you remind yourself that "anxiety is just my hardening-off process, that the symptoms will peak and subside like they did before, and that feeling anxious doesn't mean I'm doing something wrong—it means I'm practicing something new," you're creating the exact conditions that allow habituation to work.

The Difference Between Surviving and Thriving

You know the difference between a plant that's merely surviving versus one that's thriving. A surviving plant maintains itself but doesn't expand or produce. It stays in defensive mode. A thriving plant puts out new growth, flowers, shows strong color.

Right now, you're maintaining your relationships, your activities, your responsibilities. You're surviving. But you've identified what's missing: "I've been in defensive mode in my relationships—maintaining them but not letting them deepen."

Thriving means doing things because you genuinely choose them, not because you're fleeing something else. It means being vulnerable enough in friendships to share something real when they ask how you're doing, instead of deflecting to "fine, how are you?" It means sitting in the garden you maintain without working—purely experiencing it—even when every fiber of your being wants to get up and be productive.

These aren't big, dramatic changes. They're small, graduated steps. One day longer in the outdoor conditions. One degree more vulnerable in a conversation. Fifteen minutes of sitting instead of working.

But each one teaches your nervous system something new. Each one weakens an old threat entry and writes a new one.

How to Practice Choosing (Not Fleeing)

Here's what you can do this week:

With a close friend: When they ask how you're doing, share something real. Not the deepest trauma material—remember, graduated exposure. But something more honest than deflection. Something that feels both terrifying and manageable.

Notice what happens in your body. The heart rate might increase. That sinking feeling might appear. Your mind might urge you to change the subject.

And then practice your self-compassion script: "This is my hardening-off process. These symptoms will peak and subside like they did with the cancer content. Feeling anxious doesn't mean I'm doing something wrong. It means I'm practicing something new."

Stay with the conversation. Let the symptoms run their course. Observe the peak, then the natural subsiding.

In the garden: Spend fifteen minutes sitting in the space you help maintain, not working. Just experiencing it.

This will feel indulgent. Possibly wrong. You'll likely feel urges to get up and be productive, maybe some guilt about "wasting time."

Those urges and feelings aren't problems to fix. They're data points to observe. Do they follow the same peak-and-subside pattern as your other anxiety symptoms? What happens if you simply notice them without acting on them?

You're not being lazy. You're practicing doing something purely for yourself rather than for others. You're teaching your nervous system that you can exist without being productive, without fleeing, without circling in the protective pattern.

Track the pattern: Notice when you're choosing something versus when you're fleeing something else. The distinction isn't always obvious, but you're getting better at spotting it.

Are you calling a friend because you want connection, or because you're avoiding being alone with difficult thoughts? Are you volunteering because you value the work, or because the alternative feels worse?

There's no judgment in these questions. You're simply gathering information. Making the invisible patterns visible.

What Happens Next

As you practice staying with discomfort instead of avoiding it, you'll start noticing something: many of the behaviors you thought were just "who you are" are actually protective patterns formed during a time when you needed them.

And that raises a fascinating question.

When you're in the garden center choosing plants, you can tell the difference between a plant that naturally grows low and compact versus one that's been stunted by poor conditions. Both might look similar on the surface, but one is expressing its true nature while the other is restricted by circumstance.

The same question applies to your behaviors: Which ones are authentically you, and which ones are you grown root-bound?

How do you tell the difference? And more importantly—how do you help yourself spread into the space that's been there all along, waiting for you to use it?

That's what we'll explore next.

What's Next

Stay tuned for more insights on your journey to wellbeing.

Comments

Leave a Comment